The army ant and the nightjar: it is not a joke!

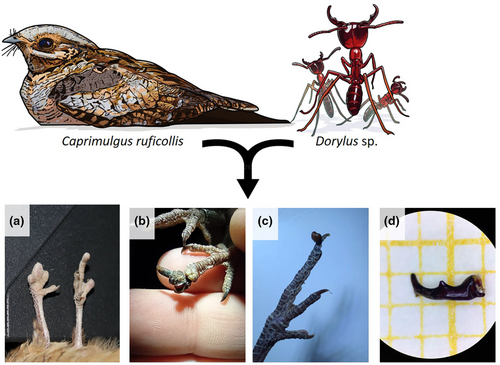

The study, “the nightjar and the ant: Intercontinental migration reveals a cryptic interaction”, by Carlos Camacho and colleagues, uncovers a remarkable and little-known interaction between migratory birds and ants. While monitoring birds in southern Spain, researchers discovered that some red-necked nightjars returned from Africa with missing toes. African army ants (Dorylus spp.) were identified as the likely culprits behind these injuries. The research presented in the following interview highlights how cryptic antagonistic interactions, often overlooked in ecological studies, may play a significant role. The project was sparked by a chance field observation and required years of systematic monitoring and collaboration with taxonomists. Although the incidence of such injuries is low, the true impact may be underestimated, as only surviving birds are observed on their breeding grounds. The study calls for more routine health checks, detailed phenotypic assessments, and photographic documentation in long-term bird monitoring programmes. Ultimately, these insights open new avenues for understanding the hidden pressures migratory birds face during their intercontinental journeys, and underscore the value of collaboration between ornithologists and entomologists.

An Interview by Olena Kolumba

Edited by Elia Guariento and Salvatore Brunetti

MNB: Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

CC: I’m a researcher at Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC) in Spain. I’m especially interested in the ecology, evolution and behavior of birds, and much of the data I use in my research comes from long-term field studies of marked individuals, such as that of the red-necked nightjar (Caprimulgus ruficollis) in the Doñana National Park in Spain.

MNB: Could you briefly outline your research on “The nightjar and the ant”?

CC: This study wasn’t part of our main research focus, but it offered a unique opportunity to look into a fascinating and little-known form of interaction between migratory birds and ants. Over 15 years of individual-based monitoring in southern Spain, we came across rare cases of adult nightjars with missing toes. After looking closely, even analysing the ant remains stuck to the injured toes, we identified African army ants (Dorylus spp.) as the likely cause. Remarkably, some ant mandibles were still attached to the birds after migrating all the way from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe.

MNB: What is the take-home message of your work?

CC: The fact that army ant bites can lead to toe amputations and potentially affect a bird’s survival suggests that interactions between ants and birds might be more important than previously thought. It highlights the need to look more closely at these cryptic interactions in ecological studies.

MNB: What was your motivation for this study?

CC: The initial motivation came from a surprising field observation in 2015 of a nightjar with what appeared to be an ant mandible embedded in its toe. This unexpected find prompted us to look more systematically at foot injuries in nightjars, eventually leading to the discovery of a pattern linking these injuries to tropical army ants. However, it took me six long years to find a full head I could identify to solve the mystery!

MNB: What was the biggest obstacle you had to overcome in this project?

CC: The rarity of injuries made it challenging to collect enough data to draw robust conclusions. Additionally, identifying ant species based on partial remains (such as mandibles or heads) is difficult, especially when the relevant genera are undergoing taxonomic revision. We also had to be cautious in interpreting injuries and distinguishing them from trauma caused by other factors, such as accidents or predators.

MNB: Do you have any tips for others who are interested in doing related research?

CC: Yes — pay attention to details that might seem insignificant during routine fieldwork. These can lead to important ecological insights. Also, whenever possible, incorporate systematic health checks and photographic documentation into long-term monitoring programs. Collaborations with taxonomists or entomologists are also extremely valuable in identify cryptic agents of injury or interaction.

MNB: Where do you see the future for this particular field of ant research?

CC: There are lots of opportunities to learn more about ant-vertebrate interactions, especially in tropical ecosystems where both groups are common and diverse. As more ornithologists and ecologists work across migratory routes and incorporate detailed phenotypic assessments into their studies, I believe we will uncover more of these hidden relationships. This could inform not only our understanding of cryptic species interactions but also the evolutionary pressures shaping the behavior and life history of birds.

Recent Comments