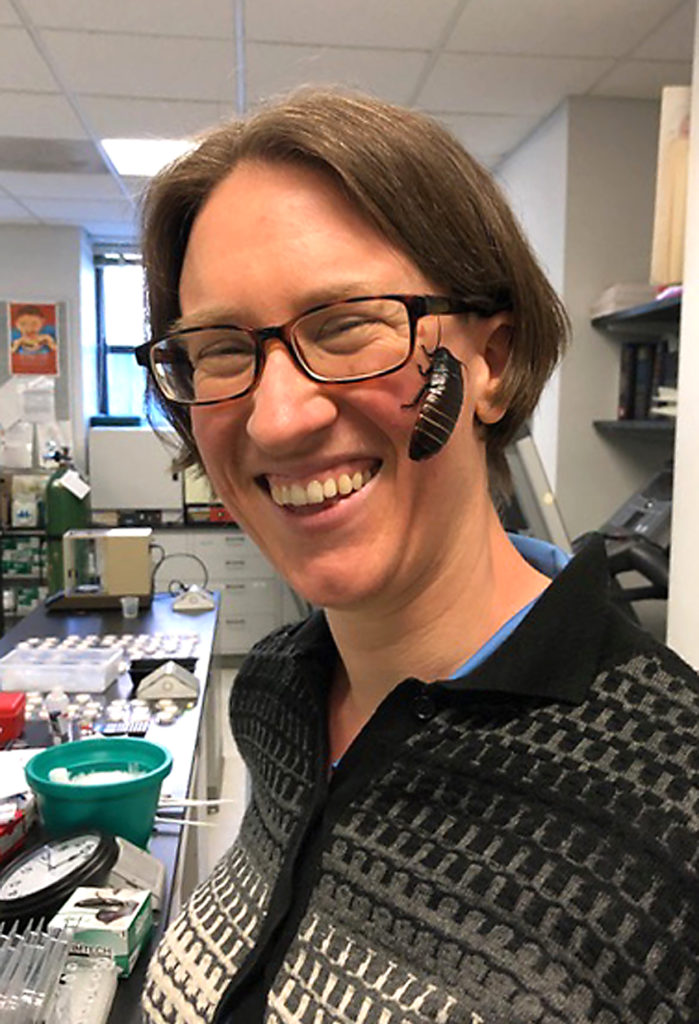

Interview with Rebecca Clark

Rebecca Clark is an assistant professor in Animal Physiology at Siena College – a liberal arts college in New York (USA). Her research, in general, is studying nutrient regulation and metabolic physiology in insects. She works both with solitary insects like crickets and social insects with a main focus on leaf-cutter ants and desert seed harvester ants. Here, she shares how she managed to collect 2500 leaf-cutter ant queens, how she fell in love with ants, and why she always makes sure not to be alone during fieldwork.

An Interview compiled by Sheethal Vepur Ramamurthy

MNB: How did you end up studying ants?

RC: I actually started with ants in grad school. I got interested in how ant colonies function as a distributed network system and was also interested in questions about how collective groups manage nutrient regulation. In an ant colony or social insect society, individuals don’t feed themselves directly. They are dependent on foragers getting information about the state of the colony and then making decisions about what to collect. In the case of leaf-cutter ants, they’re not feeding on what they bring back directly. They are feeding food to a fungus garden. So, there is an extra level of complexity to nutrient regulation in insect societies. I thought that was really fascinating. Over the course of my PhD, I got interested in the regulation of protein and carbohydrate intake in particular, which are critical for energy supply and growth. I found that although it is possible to study questions related to that in social insect colonies, it would be useful to learn more about the tools that can be used to study nutrient regulation in a simpler system. So then I got an opportunity to do a postdoc in Spence Behmer’s Lab at Texas A&M University, where he has done some social insect research along with orthopterans research, crickets and grasshoppers, and has an extensive background in nutrient regulation. So, I felt crickets sounded like a good system to learn more in a short time frame as you can breed them in captivity, their generation time is around 2 months, and it is, therefore, easier to study fitness-relevant questions. I also did some work with Ulrich Mueller at the University of Texas, Austin. He is interested in the co-evolutionary relationship between fungus and the ants. He studied genetic variation in different fungus strains. We figured out that there are two main genotypes that the desert species grows. But we still don’t know anything about the differences between those two genotypes.

MNB: Quite interesting! What was the biggest obstacle you had to overcome in ant research?

RC: I think the best story is about getting the queens I needed to start colonies. The leaf-cutting ants only mate after it has rained over an inch during the summer monsoon season, and monsoon rains in Arizona are patchy. So, you never quite know where it will have rained enough. When I got to Arizona, there were a couple of people who had previously worked on leaf-cutter species that I was studying. But some of the areas where there had been a possibility to get queens had since been developed, so there are no colonies anymore. And in other areas, Arizona had been in a long-term drought for about 10 years and so in the places where there used to be abundant colonies they weren’t abundant anymore. We had one long-term field site that was a 45-minute drive away from where I lived. So, for my 1st year anytime it rained a drop I would go out and check if the colonies had started swarming. One time when it had rained enough, we went to check some of the mature colonies. We saw queens come out of the colonies and take off in flight, and they flew towards the road, and then we completely lost track of them. So, altogether it took me three summers to figure out a location with a denser population in Tucson, after driving for hours and hours just looking for where to go. In the city of Tucson, they have a set of rain gauges that are online and so you know exactly where and how much it has rained, which meant I could check the rain gauges early in the morning before the flight would start and if it rained enough then I could go to Tucson and have a good chance of finding queens. When I finally reached the point where it rained, I went straight down and finally found a mating swarm, and it felt like I had won a lottery. At that point, I was on the verge of thinking I had run out of time to collect queens, so I would need to switch to another species and another project instead. It was really at the last possible moments that I collected 2500 queens, and I was so excited about getting them. And so I set up hundreds of nests. After going through all of that I’ve had multiple people ask how to collect queens and start colonies, and they have also run into the same kind of roadblocks – of not getting the queens. There are some tricks but if you don’t have colonies it really limits to what you can do.

MNB: Wow, that must be unnerving at times. Who or what inspired you to pursue a career in myrmecology?

RC: This is also a fun story. When I was an undergrad I didn’t know much about insects at all, I was just interested in animal behavior in general. And so I took a class in animal behavior during my junior year in college and got fascinated by social insects after we watched a film on termites called “Castles of Clay”. We also watched a documentary on Army ants, and it was interesting, but I didn’t know anything else about ants. At the same time, I knew I wanted to keep studying science and behavior. So, when I applied to different graduate programs, I applied to the program at Arizona State to work with my PhD advisor and said I’m interested in social behavior but my background is in neurobiology, studying the biochemical basis of behavior. I talked to her about what my interests were, and she said ‘yes, this could be a good fit for you’. With that, I got into the program. But when I started grad school, I still wasn’t sure about insects and wasn’t even comfortable picking up ants. But in the first couple of months, while I was learning about social insects, I got totally hooked on them. I remember the very first time I went out in the desert to look for leaf-cutter ants it was actually by myself, walking around in an area where the ants were supposed to be and looking at the ground it was just wow! There are so many different holes in the ground with so many different insects and different types of ants that are going in and out of the holes. They were just amazing. I had never experienced that before. I grew up in Seattle where there are some ants, mostly Camponotus around our house, pavement ants, etc., but I had never paid attention to them. Once I started paying attention to them, they were a lot cooler than other things that I had learned before. So, my PhD advisor Jennifer Fewell was definitely a big part of getting me hooked on ants. One other person who really helped is Bob Johnson. People know him as PogoBob because his specialty is studying Pogonomyrmex. Bob taught a course on the ants of Arizona and that was my chance to learn about the biodiversity of ants in Arizona. He would take us on ant collecting trips, and we would often have other people come through Arizona to collect particular species of ants, and he would invite graduate students to come along with them. In this way learning about all the different species of ants was absolutely fascinating. It was a lot of fun and made me look at the natural world differently. Another good thing to know is that although a lot of people discover a love for insects when they are very young, that’s not always true and it’s never too late to discover the love for ants.

MNB: If you had not become a myrmecologist, what else would you have liked to become?

RC: It’s hard to say, I might have done something art-related. While I was in graduate school I also took some ceramics classes. There was an amazing ceramics program in Arizona and I fell in love with it. I’ve always loved art, and so I would say something with art.

MNB: That’s pretty interesting! Do you recollect any funniest or scariest moments during your research that you would like to share with us?

RC: I think the scariest might win. This goes back to when I first started studying leaf-cutter ants, and I was trying to figure out field sites. I went out to a field site that was 45 minutes away. It’s in the desert, and I was walking around looking for mature colonies. The person who originally showed me the field site had warned me that there are a lot of rattlesnakes in that area. So, while I was walking around I heard a rattlesnake start rattling at me. But I couldn’t see where it was and nothing happened. Then I had the thought: if I had got bitten I will have to drive myself to the hospital to get taken care of, so this is probably not the best place to do field work by myself. Nothing happened, thankfully, but it was scary enough to make me think that there should be a better rule in place that if you are going for fieldwork you should bring at least one other person with you no matter what you are doing. After that, I just made sure that there is always someone who comes along with me.

MNB: True! Instances in fieldwork are sometimes unforeseen. But, it is good to be always prepared. Is there any particular situation in which you typically have the crucial idea for solving a difficult problem?

RC: Two types of problems come to mind – one is while trying to design how to set up a new experiment. I often run into this kind of problem if something doesn’t work the way I initially expected it to – what do I do differently? The other big type of problem for me is often trying to think about how to write about a topic, more of a conceptual problem. For both of these problems, I think the thing that has been most helpful for me is usually when I am out on my bicycle, I think about how do I solve whatever it is that I am struggling with. Just moving along, trying to get somewhere but I can let my mind wander a bit and I think exercise increases blood flow to your brain, and so I think a lot of my best ideas have happened when I’m on my bike.

MNB: Looking past, what are the main differences regarding research when you started as a myrmecologist compared with today?

RC: There has been a real increase in interest in more diverse species, and I think myrmecology as a whole has grown from when I started studying ants to know. To give one example, there are so many molecular tools that people are applying to all kind of study systems. When I started grad school a lot of those tools were limited to a handful of study organisms like fruit flies, rats, and mice. When I got started people were just starting to use microsatellites to genotype organisms, and now we have entire ant genomes. There is so much information from genome sequencing and it’s not just the genomes of a couple of ant species, you can even do comparative genomics now. I think there was a time when people thought that we would be able to solve problems by sequencing all these genomes and comparing them. But we have just discovered that there are new sets of problems and questions instead. We are very much in a period now of functional genomics. And there has been increased interest in species that are easy to rear and breed in the lab. I don’t think people were talking about clonal ants when I started studying ants. One can study many questions with clonal species that are hard to study with the conventional ant species. In addition, the species that I worked with are distinguished by having queens that cooperate to form nests. When I started, I think that was seen as an unusual behavior but as people have continued to study a wider range of species we have come to recognise that maybe it is not so unusual. Lastly, when I started we were barely starting to think about the formation of supercolonies in California and throughout the world in general. So, there is a big shift in how we think about ant societies.

MNB: What do you think will be hot topics in ant research in the next ten years?

RC: I’m going to say signaling and coordination. Historically, these have been heavily studied topics – understanding pheromone communication. But now we are at a stage where we can pinpoint more of how signaling works and I think these topics will still continue to be huge research areas studied from new angles with the molecular tools that are now available.

MNB: For people starting out new in myrmecology, do you have any suggestions?

RC: Think outside of the ant. This can be a difficult thing to sometimes hear when you are really hooked on how fascinating ants are. But, I think it’s most useful to study ants from a broader perspective of how insects work in general, what insects do across different environments. In fact, there are a lot of ideas from research outside of myrmecology that could inform and enrich research on ants. Part of this suggestion comes from my own experience of working on both solitary and social insects.

MNB: On the same lines, could you tell us about how you have taken inspiration from crickets and applied it on ants?

RC: One of the biggest things for me was to learn about nutrient regulation through crickets. In a classical method for studying nutrient requirements in most organisms, particularly for macronutrients like proteins and carbohydrates, you can offer an individual a choice between different foods that vary in both these contents. Most animals can detect how much protein and carbohydrates are there in the food and will select between foods to obtain an optimal ratio of both. So, I suggested this idea to a graduate student to study regulation in leaf-cutter colonies, by offering colonies diets that have different ratios of proteins to carbohydrates and let the colony self select its optimal ratio. A challenge has been that while there are some parallels between how an individual and a colony chooses what it eats, in a colony the ants will often also store food sources. So, it’s kind of useful for perspective on thinking about how nutrient regulation can vary between different organisms.

MNB: Considering gender equality is a topic that has been seen all over, what do you think will be most important for achieving gender equality in this respect?

RC: I think one of the hardest stages is during the postdoc. There are a couple of challenges. One challenge is thinking about what it means to have a career in myrmecology. From a direct perspective, a lot of myrmecology is basic biology, so if we limit our view to just that and look at career options it seems there are aren’t that many options available which is really discouraging and often women wind up being more discouraged than men when facing that type of information. But to counteract that, one of the first things that we need to think is that a career in myrmecology can take many different shapes and forms. We have to think about opportunities to do applied work in addition to doing basic research, and work outside of academics. So encouraging people who are in their early career to explore a wide range of career possibilities is really important because that extra level of encouragement might seem trivial but it can make a huge difference to people at crucial points in their career. The other big challenge is at the postdoctoral stage how do you move through it and winds up being different from person to person. Just knowing that can help a lot.

MNB: On a lighter note, what would you do differently if you could start all over again?

RC: I think I would have been more strategic about asking for help. I think I got stuck when it came to figuring out how to design the experiments that I needed to conduct and I didn’t really know how to go about the whole process of coming up with good questions and designing effective experiments. I was a little too shy about asking for feedback on how to make a good experiment and so, as a result, I did a number of labor-intensive, unnecessary experiments, but I learned a lot from them. I think I could have had more effective experiments had I known and gone to ask a wider range of people for help through that process. And that would have helped me to be more strategic with my time.

MNB: What question are you asked most often when people hear you work with ants?

RC: It boils down to “What’s the purpose of ants or how do I get rid of them?” My answers are: Ants are tremendously ecologically important. Insects, in general, have been under-appreciated for their ecological roles. I think there is growing recognition of that now, especially with the evidence that insect populations are declining. A lot of people don’t think about how important it is to have organisms that are recyclers, and ants are huge for nutrient cycling and soil movement. And for the ‘how to get rid of ants question’, my usual answer is “I’m generally not trying to get rid of ants, I’m generally trying to keep them alive!” I’m empathetic with people that are annoyed by ants getting in the wrong places, and so I generally suggest encouraging the ants to go elsewhere. Usually, they are in a place where you don’t want them because there is something that they want like food or water. But if you are careful you can encourage them to go elsewhere

MNB: Do you have a favorite morphological structure / myrmecological phenomenon?

RC: That’s a tough question (chuckles). I’ll have to say I really like Pogonomyrmex for their psammophore (the basket of hairs under their chin). Because the queens of Pogomyrmex carry soil, during colony foundation, in their psammophores and carry them up to the surface.

MNB: Do you have a favorite ant species?

RC: That’ll have to be the leaf-cutters that I study – Acromyrmex versicolor. People usually think of leaf-cutters as tropical but Acromyrmex versicolor is found from California to Western Texas in very dry habitats and it’s a species where there is also cooperation among queens during colony foundation. From going to collect queens and studying colonies in the wild, I just really love watching them.

MNB: Now for some short and quick questions. What is the book on your bedside table?

RC: There’s this book about Woodworking that I’m really enjoying – Tage Frid teaches Woodworking.

MNB: Watching sports or doing sports?

RC: Doing sports, no question. Like cycling and rowing. I think science takes a long attention span and so do endurance sports. So they go together.

MNB: Listening to music or playing an instrument?

RC: Playing an instrument – the piano.

MNB: Do you enjoy the evening or the morning?

RC: Morning

MNB: Tea or coffee?

RC: Coffee

MNB: Habit or change, what do you prefer?

RC: Habit

MNB: Cooking yourself or going out having dinner?

RC: Cooking

MNB: Aspirator or forceps?

RC: Aspirator.

MNB: Fieldwork or lab?

RC: Fieldwork.

MNB: Pin or ethanol?

RC: Ethanol. I’m too lazy to pin. (Chuckles)

MNB: Paper printed out or reading on the laptop?

RC: Paper, I do most of the reading on the laptop now. But I like paper better.

MNB: Journals financed by the author (open access) or by the reader (subscription-based). What do you prefer?

RC: Open access

MNB: Kin selection or group selection?

RC: (Laughs) My answer is you can use the Price equation as appropriate.

MNB: Do you prefer monodomy or supercoloniality?

RC: Monodomy

MNB: Do you prefer the workers or the queens in an ant colony?

RC: My decision is influenced by studying queens that are semi-claustral. So, I’m going to have to go with queens.

MNB: Thank you for this lovely interview. It was a pleasure getting to know about your research and love for ants!

Recent Comments