A fungus garden for a new ant queendom

Below: Co-authors Tatiane A. Sales, Antônio M.O. Toledo, and Arthur Zimerer

In the recent article “Foraging for the fungus: why do Acromyrmex subterraneus (Formicidae) queens need to forage during the nest foundation phase?” by Tatiane A. Sales, Antônio M. O. Toledo, Arthur Zimerer, and Juliane F. S. Lopes published in Ecological Entomology, the authors investigate the foraging activity during the delicate nest foundation phase in semiclaustral A. subterraneus. They applied three food-availability treatments and experimentally investigated several life-history aspects. Starved queens died earlier, but queens with easy food availability had a higher rearing success. Here Juliane F.S. Lopes highlights the main points.

An interview compiled by Alice Laciny, Patrick Krapf, and James Trager

Featured image by © Paulo Robson de Souza (CC by NC), retrieved on 29.12.2021 from https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/63715418

MNB: Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

JL: I’m Juliane Lopes, a researcher, woman, mother, grandmother, professor, drummer, and coordinator of MIrmecoLab. I have been investigating the behavioral ecology of leaf-cutting ants since 1997 when I started my master of science course at UNESP – Botucatu in Brazil, where I also later completed my PhD. Since 2005, the main focus of my studies at UFJF has been to understand how leaf-cutting ant workers, queens, and males organize themselves, share information and succeed to make a colony operate in such an amazing coordinated and efficient way. This is always accomplished together with students from both the Biological Sciences Course and the Graduate Program in Biodiversity and Nature Conservation.

MNB: Could you briefly outline the research you recently published in layman’s terms?

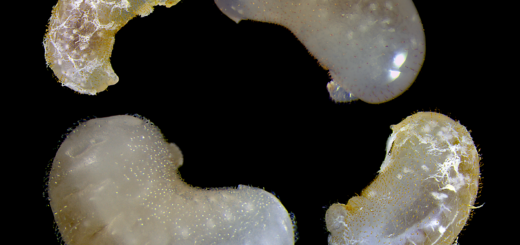

JL: In some species of leaf-cutting ants, queens are semiclaustral, which means they go out of the nest during the foundation phase. In our research, we were trying to estimate the price that these queens pay for the accomplishment of this activity. So, we simulated three conditions: “Spoiled” queens did not have to walk to obtain the plant substrate for fungus culture; “Walker” queens had to walk 6 m to collect the substrate and return to the nest; and “Starved” queens did not have access to any substrate. For each queen, we measured their weight, body energetic reserves and water content, and the number of eggs, larvae, and pupae produced until the emergence of the first workers, from which we also took body measures. For the duration of the experiment, we registered queen deaths to calculate their survival rate in each of the three imposed conditions. All these measurements allowed us to estimate the cost of the suppressed foraging steps. We verified that the survival of “Starved” queens, which did not lay eggs, was lower than that of “Spoiled” and “Walker” queens, although weight loss, water content, and lean dry mass were similar. While lipid content reduction was similar for “Spoiled” and “Walker” queens, the former had more larvae and pupae, and a heavier fungus garden than the latter, suggesting a greater rearing effort of “Spoiled” queens towards both the brood and the food garden. The simulated foraging conditions provided novel data for semiclaustral leaf-cutting ant queens that provides evidence that fungus garden cultivation is definitively the main driving force for colony-founding success.

MNB: What is the take-home message of your work?

JL: That the fungus garden culturing is the key to the success of colonies in the foundation phase. If the queens can’t feed the fungus, they may survive but will be unable to produce their offspring. The verified association of the queen’s foraging and fungus development with the success in this colony phase contrasted notably with other studies on semi-claustral ant species, which report that queens cannot survive without foraging.

MNB: What was your motivation for this study?

JL: We were curious to evaluate the importance of different steps of the queens’ foraging activity and how each of these steps is related to the success of the colony, considering that less than 5% of them survive the foundation phase.

MNB: What was the biggest obstacle you had to overcome in this project?

JL: As we had to run the simulation with 90 queens at the same time, it was a great challenge to make an experimental setup that fits into the lab space and at the same time would be as close to field conditions as possible. The management of the “Walker” queen colonies was the hardest, as these needed to be coupled to a path long enough for the queens to forage.

MNB: Do you have any tips for others who are interested in doing related research?

JL: Collect as many queens as possible during the nuptial flight, as their mortality rate is very high. Care for the queens in the lab as if they were newborn babies, to improve their survival and avoid unnecessary manipulation.

MNB: Where do you see the future for this particular field of ant research?

JL: Verifying if queens have an alternative strategy when faced with the death of the symbiotic fungus. Are they able to steal the fungus from other colonies? Is this one of the causes of the polygyny reported for these ant genera?

Video: Behaviour of a foraging queen

Recent Comments