Ants Among Mesoamerican Ruins

In January 2020, before the corona crisis, I was lucky to have had the opportunity to go on a two-week short trip to Mexico. My travel was a small holiday focused on experiencing different aspects of Mexican culture and getting some quality beach time. However, I just couldn’t resist and had to look for ants most of the time! So here, I want to share my anting impressions of this large and diverse country that is famous for its ancient ruins and harbors an impressive ant diversity. This photoblog entry thus became an odd mixture of some famous Mesoamerican ruins and the coolest ants around them, and I hope you enjoy it!

A Photoblog contribution by Phil Hönle

All pictures are © Phil Hönle

1. Mexico City

Did you know that there is a part of Mexico City called Azcapotzalco, which literally translated from Nahuatl means “in the place of the ant hills”? Even the old Aztec glyph for the municipality depicts a red ant surrounded by corn. Coincidentally (or not?), Azcapotzalco is the hometown of my girlfriend and bee researcher Gemma Villagomez, and the very first place I visited after arriving in Mexico.

Not too far from the giant city, we seized the opportunity to get an impression of how this region may have looked in the past. We went to the world-famous pyramids of Teotihuacan, which were established by a civilization that died out long before the classical Aztecs were around. They left one of the world’s highest pyramids surrounded by many impressive ruins, in what is seemingly an unproductive shrubby desert landscape. At the foot of the pyramids, we could see one of the most infamous desert ants roaming around, the big red Pogonomyrmex barbatus. These are seed harvester ants, and they were looking around for food seemingly unimpressed by the old structures around them. I liked to imagine these ants crawling around the feet of the ancient humans, then and now as uninterrupted in their seed harvesting business as always.

In a nearby restaurant, I got to try a local food specialty that can apparently be traced back to the Aztecs: So-called “Escamoles”, cooked ant brood from Liometopum ants. Liometopum are known for their strong chemical defense, and the ant brood has, therefore, an intense taste, which was surprisingly delicious. And by the way, in the other bowl are the caterpillars of an Agave moth (“gusanos de maguey”).

2. Chiapas

After this short but intense experience with the arid region, we traveled on to one of the most humid places of Mexico, the state of Chiapas. It has a calm, rural landscape that encompasses many of the most untouched rainforests of Mexico. Further, it is known for several huge Maya ruins and several indigenous communities that are still existing today. Our trip led us to the Northern part of Chiapas, to the ruins of Palenque, which are overgrown by a disturbed, but still relatively mature, rainforest. Today, it is a big tourist attraction, but it was very pleasant to walk as the area is enormous and there are lots of paths leading through the forest.

To my joy, the place had an impressive diversity and abundance of ants. Under a stone, I found a nest of the fungus growing Apterostigma. I could not identify the species, putting it closely but still distinct from A. chocoense. After contacting the expert Jeffery Sosa-Calvo it turned out that it was an undescribed species that was already known to him.

On a tree, I spotted a little Camponotus species called Camponotus rectangularis. They have a beautiful orange coloration and curious eyes.

Close to our lodge, we saw an army ant raid of Labidus praedator, and when we returned in the night, we found them migrating close by. Migrations of this species are not as easy to observe as those of Eciton, because they are often subterranean. But here, on a small stretch, we could see one street where the army ants were carrying their brood. Patiently, we sat down – army ant migrations give the unique chance to see the coolest of myrmecophiles, following along. And indeed, we spotted several myrmecophilous millipedes! Probably they belong to the genus Calymnodesmus (thanks to Christoph von Beeren & Daniel Kronauer for the ID suggestion). Not much is known about their lifestyle, but presumably, they feed on dirt & leftovers inside the army ant nests. It must be quite a lot of work to follow the migrating ants to new places every few days.

Now, we have seen the northern part of Chiapas, but the most thrilling part was still lacking – the humid mountain forests not too far from the Guatemalan border. With a rather adventurous bus drive that took us many hours, we curved deeper and deeper into the mountains, every few hours passing some rural villages. Eventually, we arrived in the reserve Nahá, where a native community of Lacandon Mayas was running an Ecolodge.

The nature here was stunning, but it was also cold and rainy. This meant that the anting would be a bit more of a challenge, and the ant abundance was comparatively low. But every now and then we would spot some of the amazing ant species that live there. Most common was the charming Pheidole biconstricta (thanks to Jack Longino for the ID) that could be observed tending planthoppers for their nectar. In one instance, I found an incipient nest inside a log, and her majesty was not amused by my paparazzi photoshoot. [In a former version, the ID of the species was wrong]

We saw a specimen of the arboreal genus Procryptocerus walking up on the stem. The worker carried an egg, and I wondered if this was it’s own or if it was stolen from somewhere.

Near the swamp, I spotted a Cephalotes porrasi worker disappearing into its nest in the twig. Curiously, it was hard to spot the nest entry – I knew a major would block the nest entry with its head, but I did not anticipate the absolutely masterful camouflage of this specific individual. Its exposed part of the head was rough, like bark, and it had a piece of moss as well as lichen growing on it! The cuticular structure of the head has been researched by Wheeler and Hölldobler (1985), and they discovered that head glands produce sponge-like tissue on the head which serves as camouflage. But as far as I am aware, no one ever reported individuals with moss growing on their head. I carefully opened the twig, which indeed contained part of the nest. Unsurprisingly, the other majors inside did not have anything growing on them. After taking pictures, the nest was placed back on the tree.

After some hiking and taking apart a lot of dead wood, I also encountered a typical Ectatomminae species: Typhlomyrmex rogenhoferi, which forms surprisingly large colonies. The colony had males, and the head of one can be seen in the following picture poking in from the upper left corner. A species from the subfamily Amblyoponine was also there: quite minute, with barely 2 mm of body length – it was a Prionopelta species, I believe P. modesta. [In a former version, Typhlomyrmex rogenhoferi was mistakenly assigned to Amblyoponine)

As in the lowlands, we encountered an army ant raid of Labidus praedator. I enjoyed spending some time among the raid because watching them can be mesmerizing. One can hear the thousands of ants scrabbling through the forests leaf-litter, as well as the larger insects fleeing the front. And then there is always the humming of several parasitic flies, that try to lay their eggs onto some of the fleeing insects. It is always exciting to see the varying strategies of animals dealing with army ants.

The caterpillar on the picture, however, did not have a successful strategy and ended up as dinner.

Amidst the army ant raid, I spotted a staphylinid beetle with an untypical behavior. Instead of running away from the army ants as many other of the staphylinids, he just stood still among them, his body raised in alarming form. Several times the Labidus would run all over him, only to retreat shortly after. His strategy seemed to work, and he was left unharmed. Curiously, I contacted the Staphylinid expert Joe Parker about this beetle, and he explained that this was probably a member of the genus Paedarus, which have poisonous hemolymph – which is why the army ants would not eat it. Somehow, they were able to tell just from smelling the cuticula.

3. Yucuatan Peninsular

After these adventures in the cold and rainy mountains, we continued our travel back up north, into the southern part of the Yucatan peninsula to enjoy some sun after the cold mountains. Here, we visited the huge reserve Calakmul which contains big Maya ruins of the same name. The forest was quite different from what we had seen before – the terrain was completely flat and rather dry. When we climbed on top of the pyramids, we could see in all directions – only forests, and the only peaks in the visible distance were other ruins sticking out of the canopy. It was an incredible view! Here, we saw many ants, most notably several raids of the Northern subspecies Eciton burchellii parvispinum.

Our stay was short, and we continued to the North-East towards the Caribbean coast. In Tulum, another famous place for Maya ruins directly at the sea, the forest changed further, the trees became overall smaller and the landscape drier. The sunny coastline offers a superb habitat for many arboreal ants that like a lot of sun, such as this Cephalotes cf. pusillus that I found directly next to the Maya ruins. [In a former version, Cephalotes cf. pusillus was erroneously written].

In the night, we watched a migration of Neivamyrmex sp., with each worker carrying the doryline – typical elongate larva beneath their bodies. [In a former version of this post, Neivamyrmex sp. was mistakenly identified as Neivamyrmex gibbatus. We thank John Lattke for clarifying this.]

Whilst opening up some twigs, we found a variety of beautiful ants, mainly Camponotus species. For instance, here is an unidentified, quite hairy species. They were watching me with great suspicion.

But what I really wanted to see there were the infamous swollen-thorn Acacia trees with their symbionts of the Pseudomyrmex ferrugineus complex. And indeed, after a little bit of searching, one after the other showed up. Their thorns are domatias – specialized plant parts that serve the ants as home. Furthermore, the trees have many nectaries, which provide their ants with delicious carbohydrates. And, to supply their larva with protein, the trees have specialized leaves called Beltian bodies. The ants do not need to take in any additional food resources. In return, they kill any herbivores that want to take a bite of the Acacia, and they even show aggression towards other plants in the vicinity, which might overgrow their plant.

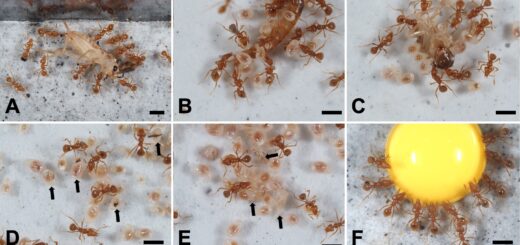

To have such a nice plant home and be self-sufficient, the queen have to overcome the critical colony foundation phase… After mating, the winged Pseudomyrmex queens need to find a plant that does not already have a colony on it, i.e. a young plant that just started producing its first couple of thorns. When I opened the thorns of such a small plant, I found several queens in each of the thorns. However, only one will eventually take over the plant – so there can be fights between them. The queen on the picture might have already suffered from such a fight, having lost a tarsus. Often, several colonies are being raised at the time at the same plant, with one colony eventually outcompeting and killing the others (although there are also polygynous Pseudomyrmex species known that inhabit swollen-thorn Acacias).

What a brutal upbringing of an otherwise vegetarian, tree-worshipping “hippie community”!

Our journey ends here – although we barely traveled two weeks, it felt a lot longer because there was so much to experience. Mexico has been a pleasure to see, and not just the many ant species are a delightful sight. This country is diverse and there are so many places, and so many ants still left to see.

Thank you for sharing these wonderful photos and stories! Some of my favorite anting experiences-also just life experiences in general-have been in this beautiful country. Thank you for making me want to return!

Philip, as always your images are stunning, both technically and aesthetically. Ants with Mayan and Aztec backgrounds. Demasiado bueno. Gives me a reference point to look up to. My only quibble is the Neivamyrmex ID, that is not gibbatus. I am not sure what it is, but gibbatus has an angular drop from the mesonotum to the propodeum and another angle between the dorsum and declivity of the propodeum.

Thank you John! You are absolutely right, this isn’t N. gibbatus. We will correct this 🙂

Best, Phil