Interview with Jonna Kulmuni

Jonna Kulmuni is an Academic Research Fellow and Principal Investigator at the University of Helsinki in Finland. She is broadly interested in understanding evolution and speciation acting in natural populations and focuses her research on hybrid wood ant populations (Formica rufa group). Here, we talk about her recently granted funding, her master’s in science communication, and why she loves evolution in ants.

An Interview compiled by Patrick Krapf

MNB: Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your research?

JK: I have a research group at the University of Helsinki, and we are currently six people in our lab. All of our questions revolve around understanding hybridisation and speciation and using mound-building wood ants as our model system.

MNB: You were recently awarded a big five-year research fellowship grant. Congratulations here, of course. My question now is how did you end up where you are now?

JK: Yes, that is correct. Well, I think it was sort of an accident that I ended up studying ants because I wasn’t planning to do so. I was interested in insects, but in the beginning, I thought that I was going to study beetles. Then Pekka Pamilo happened to have a summer job for me. He is retired now, but he’s has done a big career in ant research. And yes, I didn’t know about ants then, but as I started the job with Pekka I started reading about ants. I found the popular science book by Wilson and Hölldobler, “The Ants” and got fascinated by the ants, their sociality, their communication, and their social structures. And on top of that, working with Pekka was fantastic; he was the best supervisor I could imagine. So stayed with ants as I got more and more interested and found a supportive research environment. Then I did a PhD with Pekka and half of the PhD was about the genetic basis of chemical communication in ants. The other half was about hybridization. After defending my thesis, I thought quite hard about what to do next. Would I actually change the study system? I decided that this was my niche now, as no one was working on hybridizing in ants with only a few genetic studies on speciation in ants – because most people are interested in sociality. So I continued working on the system. And since then I’ve applied for fellowships and started building my own research group. Ever since I defended my thesis, I have basically funded the research with independent fellowships.

MNB: This is extremely impressive and amazing!

JK: Yes, thank you. This current grant is the longest one I’ve had so far. This, of course, is nice so that you have a little bit more time to plan. The grant is about understanding hybridisation through time and space. The through-time component actually only becomes possible because I’ve been working on this system since my masters in 2004 and I have all the samples left from when I started working. So now, we can actually study how the hybrid population has changed over time by using samples that I’ve stored throughout the years.

MNB: Oh wow, this is great. Because you can work with data, that you created and you have all the background information. How did you come across these results?

JK: It was sort of an accident (again!) that we noticed it because the results were different than we expected when we compared newer samples with samples that were collected 10 years ago. It was a big genetic change in that time period; so it was these sorts of unexpected results that made me think about the time perspective and I decided to write a grant application on it.

MNB: Great idea, obviously. I read online that you did two master studies, one in biology and one in science communication? How so?

JK: Yes, true. I did the science communication masters at the same time I was doing my PhD. I was doing my PhD part-time, like 80%, and during the remaining 20%, I was doing the second masters. I guess I’ve always enjoyed taking different perspectives on things, this is what the science communication masters allowed me to do. That’s one component in it and the second one is that the program was fantastic. There were people from all areas of science, like chemistry, philosophy, and psychology, and we were studying together how to communicate our results efficiently and in an interesting, inspiring way. We learned about other ways of thinking. I think science communication is important and I’ve tried to do a little bit of science communication throughout my studies in the UK at the University of Sheffield, where I spent two years doing a PostDoc. There, the university community-appreciated science communication and there was actually more structure provided by the university. People were paid to help you do science communication. A really interesting project we did was with an artist and different scientists from the university. Together with the artist, we planned workshops revolving around our research and then these workshops were done together with students from poorer areas. The idea was to get people interested in science, and also that pupils from schools with lower rates of university entries get interested in pursuing a career in science

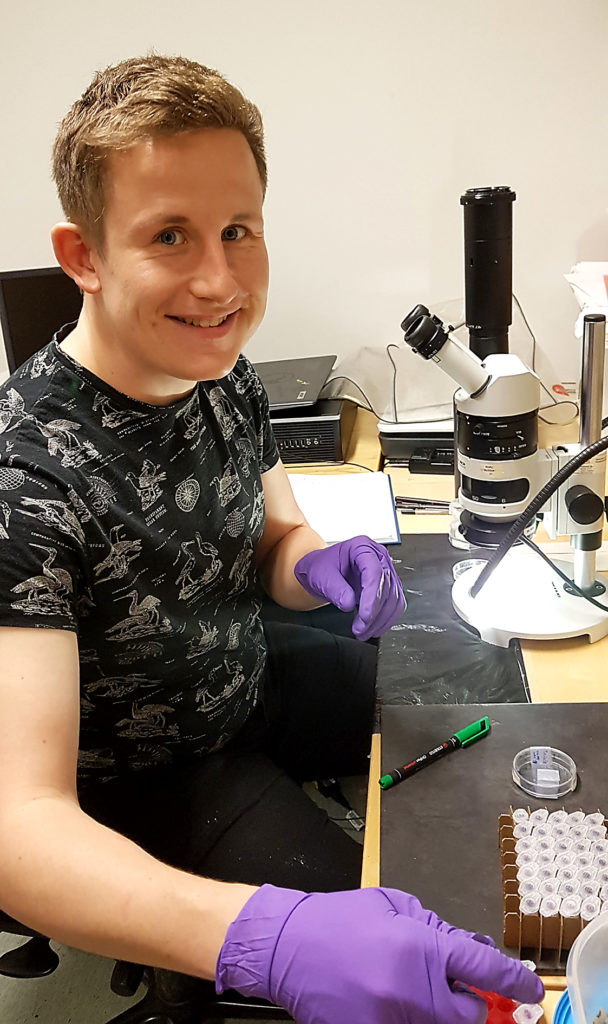

PhD student Jack Beresford has studied hybrid larvae transcriptomes in his thesis, particularly the effect of introgression on gene expression. He is currently studying if there is selective mortality in the hybrids before hatching into larva. (© Jonna Kulmuni)

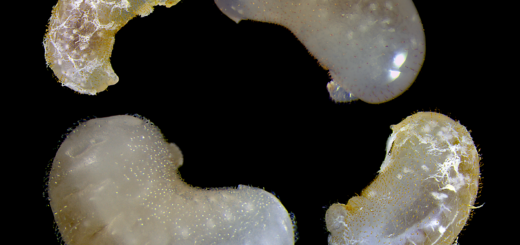

Hatched hybrid larva. (© Jonna Kulmuni)

MNB: If you had not become a myrmecologist, what else would you have liked to become?

JK: Well, good question, I don’t know. The thing that I’ve always been interested in is evolution, how it works and so on. I mean, I was lucky to end up studying evolution using ants.

MNB: What is your motivation for doing ant research now? What do you enjoy most about ant research?

JK: I guess, the most important thing for me was always to understand evolution. I’ve always been interested in understanding natural selection at all levels. So understanding how natural selection acts on mutations in the DNA sequence, how that affects the expression or the structure and the function of the protein, and that again for the phenotype of the organism and fitness, but this also in the context of the whole ecology and environment. Tracking these signatures of natural selection from top to bottom or the other way around has always been my dream. And I realized that ants are actually really good for doing that. They offer some advantages compared to other organisms. One is that in mound-building wood ants the nests stay put. You know, you can study the same population, the same nests, for decades. You cannot do this with all organisms because they are difficult to find or you don’t know whether you are sampling the same thing or not. The other thing is that we can collect high sample numbers, and if we want to measure natural selection in nature, we need to be able to compare large numbers of samples. One of my colleagues here studies reed warblers. She sometimes has difficulties in finding a big enough sample number and reaching bird 30 nests is already impressive. So compared to that, mound-building wood ants are perfect as we can sample hundreds or thousands of individuals. The other nice thing is that we can study genotypes or allele frequencies throughout development but then compare them between years as well.

MNB: So you can compare data from the same mounds and between different mounds and use this data to check for hybridization, gene flow, as an example, right?

JK: Yes, the sampling that we have used and that we will now use in our future studies is also that you can have a real-time natural selection experiment in nature, because you can collect eggs from queens, so you know the genotype before selection, and then you can collect adults who survived that year. Thus, you can collect genotypes before and after selection and by contrasting them, you can try to look at the signatures of selection in the genome. Basically, you can see where in the genome changes in allele frequency occur which are not explainable by random fluctuations or some other effects.

MNB: Wow, this sounds amazing! And when can you start your next field season then?

‘JK: So it depends on the weather because if there is snow or if the weather has been cold, it is later in the year, but now we’ve had a very poor winter with no snow at all. We will see, but maybe it is between late March and early April. That is when we can collect the old queens because they come on top of the nests to warm up there. So that’s the time you can catch the queens. You know, the mounds are huge, like several meters high, and you cannot find the queens when they are on the ground, but early in the spring, they come on top of the nest. Simultaneously, you can also collect eggs that would be the genotypes before selection has happened. And then you can follow the nest through that season. And the first brood that they will lay are the males and queens. Those are also the individuals we are interested in for our selection experiments because we know that they will experience selection during their development and that they have been born that same year.

MNB: And when does your field season end?

JK: I would say at the end of June or early July. We wait until the sexuals emerge and go on a mating-flight and that’s our last sampling period.

MNB: So it is a quite narrow time window?

JK: Yes, quite narrow, but manageable to do research! (laughing)

MNB: During your research, what was the scariest or unexpected moment?

JK: Well, I would not say scary but unexpected. My whole masters project actually started with some unexpected results that my professor Pekka could not explain, and then he asked me to go to that population again and try to understand it. So, I think part of my research has been just following this mystery, trying to understand what happens and trying to bring the different pieces of the puzzle together so that we can explain what’s happening in nature. So when I finished my PhD we thought, okay, we have solved it and we know what’s happening. But then during my PostDoc and the first fellowship I noticed that the results are not at all what we would expect and then we saw this really strong genetic change after 10 years. And again, I was at the position that now I needed to explain what is going on! And I have to say, I have never seen this as depressing, on the contrary, I always thought this is interesting. When there’s something you cannot explain or something is unexpected, this is a nice possibility to go on with your research. And you then perhaps discover something new. I mean there are many cases where you realise there’s something weird in the data – I am not talking about only my research here. But as a researcher, you come across a data in which something doesn’t match. So then, some people would throw that away. Alternatively, in the sequence data, people would throw those sequences away that don’t fit the genome assembly, but maybe there’s something interesting going on.

MNB: So quite a rollercoaster (laughing). And now with all your experience, do you have any suggestions for myrmecology newbies?

JK: I don’t know if this applies to myrmecology per se but I would say that try broaden your experience as far as possible and acquire skills working in natural populations collecting the ants, understanding their biology, their natural habitat, but then also some computational or lab skills. So combine different types of skills.

MNB: So true! Another question tying to this: Would you do something differently if you could go back?

JK: So, I think I am quite a positive person and if there is a difficult situation, I move on and try to solve it. I like my career, the steps that I have taken, but something I think is important is that when you go and do a PostDoc, you should learn some additional skills. Because the further you go, it gets increasingly difficult to learn new stuff as you do not have time anymore. For learning new skills, you cannot do it one hour here and one hour there, but you need a good amount of time to concentrate and learn. So, this is maybe something that I should have thought about more back then when I went to Sheffield. To spend more time and effort more concretely for learning a specific new skill.

MNB: Such great advice!

MNB: Slightly different topic now. The higher the career level, the fewer women, also in ant research – what do you think will be most important for achieving gender equality?

JK: As you know, I did a PhD in Finland and I am Finish, and here, there is quite a good equality between genders especially on lower levels. So, I never thought that it would be a problem to either have a family or be a female PI or something like this. But maybe I was naive because when I went to the UK, I could see that they have very strong gender roles and their gender bias is also stronger. And in the UK, I realized that a large part of my freedom was the fact that in Finland, the mother can go to work and there is child-care provided by the government. But in the UK, if you have a child and want to put that child into day-care and go back to work, it can basically cost nearly as much as one person earns. So, it’s really, really expensive, and that means that in the UK, it is usually the mother who stays at home. So providing low cost care, I think, is one possibility of how different countries can provide support for families so that men and women could have equal opportunities.

In the group where I was doing my PhD in Finland, there were three other women and all of them had either one or two kids while they were working in the group. So, I also have this positive example. I had two kids during my PhD as well. So, now, after being in the UK and coming back to Finland, I realize that there is a problem with gender bias. The small things I do to improve this is that I talk about the problem with my students and with my group. We went to a gender bias training provided by the university. And nowadays, if I’m asked to propose reviewers or if I’m choosing reviewers – whatever I do in the academic society – I aim for equal sex ratios so that there wouldn’t be a bias in the initial stages. For example, I’m involved in running the seminars for our department here. And we aim to have an equal sex ratio in the speakers that we invite. I think that we are all biased even though we would not want to be. There are these tests that you can take on the internet which measure your unconscious bias. So finding ways to try to reduce that unconscious bias is important. For me, equal sex ratio rules, for example when proposing reviewers you have to have 50% females and 50% males, are helpful, I think.

MNB: Thank you for this elaborate answer! Now, we change the subject again. So what is the one thing you wish everyone knew about ants?

JK: I mean there are so many things (laughing J). It’s difficult to say one thing. Obviously, their sociality, their importance in the ecosystems. Their amazing caste system! I guess if there’s one thing I would say their importance in the ecosystem

MNB: Do you have a favourite morphology or species?

JK: I guess I have to say the mound-building wood ants (laughing). They are so beautiful.

MNB: What is the book on your bedside table?

JK: A fantasy book by Robin Hobb.

MNB: Watching sports or doing sports?

JK: Doing sports.

MNB: Listening to music or playing an instrument?

JK: Listening to music.

MNB: Do you enjoy the evening or the morning?

JK: Morning.

MNB: Tea or coffee?

JK: Coffee.

MNB: Sugar or sweetener?

JK: Neither.

MNB: Habit or change, what do you prefer?

JK: Change.

MNB: Cooking yourself or going out having dinner?

JK: I’d like to go and have dinner but in Finland, it is so expensive, so we cook a lot at home.

MNB: Aspirator or forceps?

JK: Forceps.

MNB: Nest densities or pitfall traps, what do you prefer?

JK: I wouldn’t be comfortable with either (laughing)

MNB: Field work or lab?

JK: I would say I am more comfortable with lab work.

MNB: Pin or ethanol?

JK: Ethanol.

MNB: Paper printed out or reading on the laptop?

JK: Read on the screen.

MNB: Journals financed by the author (open access) or by the reader (subscription-based). What do you prefer?

JK: Open access.

MNB: Kin selection or group selection?

JK: Kin selection.

MNB: Do you prefer monodomy or supercoloniality?

JK: Supercoloniality.

MNB: Do you prefer the workers or the queens in an ant colony?

JK: To combat the bias, I would say males in this case, because they get very little attention in the ant world.

MNB: Thank you so much for this nice interview and for this nice chat with you!

JK: Thank you!

Recent Comments