Trophic Eggs as Exclusive Strategy for Nutritional Sharing in Black Cocoa Ants

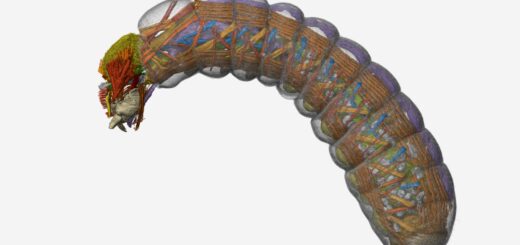

Trophic eggs are inviable eggs or egg-like structure without an embryo and are not meant for reproduction. Such eggs can be considered a form of maternal investment for their offsprings, largely for nutritional purposes. Among ant species trophic eggs can have a wider range of colony-level impacts, such as providing nutrition for colony founding and affecting case determinantion.

Trophic eggs have previously been documented as supplemental to trophollaxis for food sharing but are perceived as slower vs. trophollaxis for such purposes.

In their study, Chen and colleagues show that black cocoa ants, Dolichoderus thoracicus do not engage in stomodeal trophallaxis, a well-documented and commonly employed strategy for food sharing. The current study demonstrates the obligate use of trophic eggs for nutrition sharing among colony members. Furthermore, authors show that workers of this species are incapable of laying reproductive eggs, suggesting specialization in trophic egg production for nutritional provisioning of colony members. They have expanded on these findings to demonstrate a similar role of trophic eggs in two other Dolichoderus species and three Technomyrmex species.

Exclusive use of trophic eggs for nutritional sharing, as shown by authors, further goes on to show the different cooperative behavioral strategies that may exist among ant species.

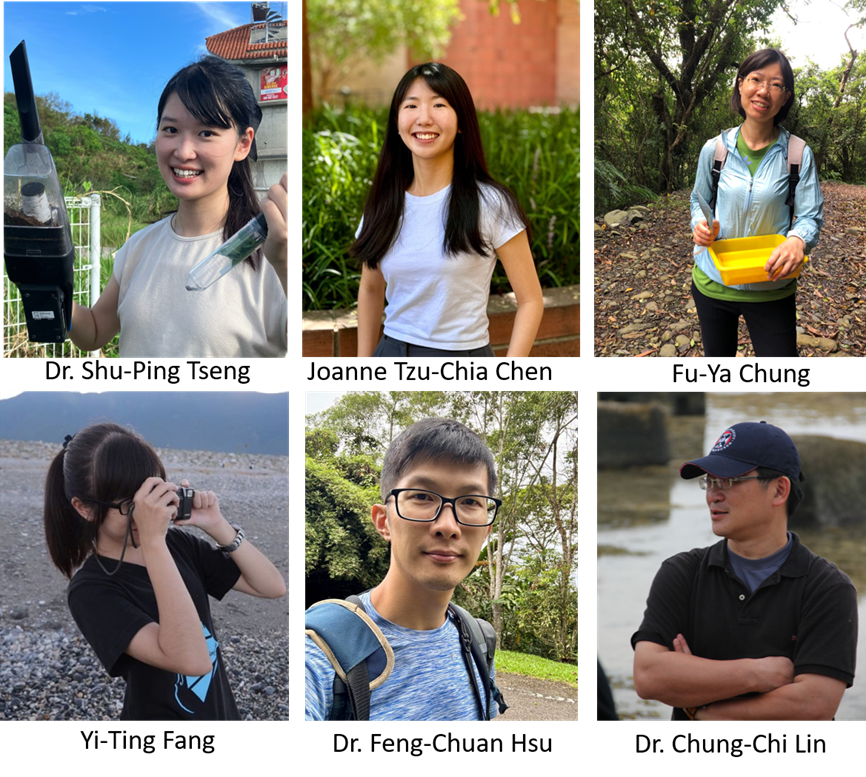

Here, Shu-Ping Tseng highlights the main points and shares some pictures of the field work.

An Interview edited by Sheehtal Veepur and Rohini Singh compiled by Salvatore Brunetti

MNB: Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

SPT: I earned my PhD from Kyoto University, where I focused on identifying the potential native range and unique reproductive strategies of a globally invasive ant, Paratrechina longicornis. Following my PhD, I served as a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, Riverside, applying my expertise in population genetics to Urban Pest Management. I investigated the infestation history, population dynamics, phylogeny, insecticide resistance, and gene expression of various insect pests. In August 2022, I joined the Department of Entomology at National Taiwan University as an assistant professor. Since joining NTU, my lab has focused on the study of urban and invasive insects, employing an interdisciplinary approach that integrates genetics, genomics, behavior, and evolutionary biology. Our primary objective is to deepen our understanding of these insects and develop effective strategies for their management. We are particularly interested in how invasive species spread on local and global scales, the factors contributing to the invasion success of alien species, how insect pests coevolve with their symbionts, such as gut microbiota, and with their nest symbionts like myrmecophiles, and the factors that lead to control failure in managing urban and invasive pests.

MNB: Could you briefly outline your research on “Trophic egg transfer in the black cocoa ant Dolichoderus thoracicus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and other dolichoderine ants in Taiwan” that would be published in Myrmecological News in layman’s terms?

SPT: Certainly! Social insects like ants have fascinating ways of sharing nutrients within their colonies, crucial for their survival and growth. Typically, ants share food through a process called stomodeal trophallaxis, where they directly transfer food mouth-to-mouth. However, our study explores an alternative method used by some ants, known as trophic egg transfer. In this method, certain ants produce eggs that are not meant to develop into new ants but are instead eaten by other colony members, providing essential nutrients. In our research, we found that the black cocoa ant, Dolichoderus thoracicus, does not use the common food-sharing method. Instead, it relies entirely on these nutritive eggs. Moreover, we report the first observations of trophic egg production in two Dolichoderus and three Technomyrmex species, expanding the known taxa with this capability. This study not only highlights an unusual nutritional strategy in ants but also expands our understanding of how nutrients can be distributed within ant colonies, offering insights into their complex social behaviors.

MNB: What is the take-home message of your work?

SPT: The primary takeaway from our study is that the reliance on trophic eggs for nutrient distribution within ant colonies may be more widespread than previously understood.

MNB: What was your motivation for this study?

SPT: The discovery that ignited this study was completely unexpected, all thanks to the keen observation skills of my research assistant, Joanne, who is also the first author of our paper. On Joanne’s very first day learning to dissect ants, she selected Dolichoderus thoracicus. As she examined this species, she noticed the ovaries of workers were unusually well-developed, suggesting something extraordinary. This led her to hypothesize that these ants might produce trophic eggs—a rare and noteworthy behavior. Inspired by her initial findings, Joanne dedicated more time to observing the ants closely. Her dedication paid off the very next day when she observed a worker ant producing a trophic egg. This moment of discovery was the catalyst for our entire project, demonstrating how scientific curiosity, sparked by unexpected observations, can lead to significant research breakthroughs.

MNB: What was the biggest obstacle you had to overcome in this project?

SPT: The most challenging aspect of this research was documenting the rare behavior of trophic-egg transfer. Capturing high-quality video evidence required a setup that combined a microscope with a high-resolution camera. This task demanded patience and precision, as the behavior could occur unpredictably and without warning. Our team spent countless hours monitoring the ants, ready to zoom in and record at just the right moment. This painstaking process was crucial for obtaining the visual proof we needed to substantiate our findings, demonstrating the dedication required in scientific research to capture nature’s subtleties.

MNB: Do you have any tips for others who are interested in doing related research?

SPT: Effective research on trophic eggs relies heavily on careful observation. When working with ant colonies, it’s crucial for researchers to allocate ample time to closely observe their behaviors. Immersing yourself in the details of your study subjects is essential. Always keep an eye out for anything unusual—keen observation is indeed your most valuable tool in this field. This combination of passion for your subject, meticulous observation, and continuous learning is vital for achieving success and making meaningful discoveries in entomology.

MNB: Where do you see the future for this particular field of ant research?

SPT: Research on trophic eggs in ants could potentially offer new insights into their evolutionary adaptations and complex social behaviors. Delving deeper into the evolutionary origins of trophic egg production is a crucial next step. Furthermore, our findings might help shape pest management strategies for ant species that do not use traditional stomodeal trophallaxis. Evaluating the effectiveness of conventional baiting programs for these species and exploring alternative control methods, such as deploying pathogens or contact-based toxicants, is essential. These approaches could be key to developing more effective pest management solutions tailored to the unique behaviors of these ants.

Back in my grad school masters degree days (mid 1970s, Univ. of Kansas), I kept a large colony of Tapinoma melanocephalum in the lab which exhibited trophic egg production and feeding to nest-mates. This was initiated by vigorous antennal tapping by the egg recipient on the mandiblular / genal area of the donor worker, followed by the donor flexing the gaster forward to produce the egg, which was more round than a reproductive egg. Both queens and workers were fed this way. It would be interesting to know how widely distributed this behavior is in dolichoderines, and in other ants. I did not observe adults feeding larvae in this manner.