Spiny ants (Polyrhachis lamellidens) parasitise Camponotus obscuripes in nature

In the short communication “The evidence of temporary social parasitism by Polyrhachis lamellidens (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in a Camponotus obscuripes colony (Hymenoptera, Formicidae)” published in Insectes Sociaux, the authors H. Iwai, Y. Kurihara, N. Kono, M. Tomita, and K. Arakawa performed various field observations and lab experiments to show that P. lamellidens is a social parasite of C. obscuripes and not only of Camponotus japonicus. They found several lines of evidence for this social parasitism. Here, Nobu Kono highlights the main points and shares some pictures.

An Interview compiled Roberta Gibson, Patrick Krapf, and Lina Pedraza

MNB: Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

NK: I am a researcher specializing in bioinformatics and genomics, and I am a Project Assistant professor at Keio University. I am interested in how living things behave and their material production capabilities, and my goal is to quantitatively understand the design nature of life starting from the genome. My research interests include bacteria, ants, mites, minnows, spiders, and rats. My study on ants began in earnest about five years ago when an undergraduate student, Iwai, joined my group; he has been a specialist in ants since before he entered the university, and although I am still a novice ant researcher, he has helped me to conduct some very exciting ant research.

MNB: Could you briefly outline the research you recently published in layman’s terms?

NK: Our most recent major achievement has been the discovery of evidence in the field that spiny ants (Polyrhachis lamellidens: Toge-ari [Japanese]) are able to parasitize Camponotus obscuripes (Muneaka-oo-ari [Japanese]). Spiny ants are temporary social parasites, meaning that they cannot establish colonies on their own. Instead, they invade and take over other ant colonies which serve as hosts. It has been suggested that C. obscuripes might host spiny ants, but there is not much evidence from field observations. Our results are not records of accidental associations found in the field. We proved by various bioassays that the parasitic state was not simply the presence of multiple species in close proximity, but that the parasitism was established. Whether parasitism is present or not depends on whether the differences are aggressive, whether they take care of their broods, and so on. For all of them, we verified the results by conducting quantitative experiments. As a result, the team was able to prove that spiny ants use C. obscuripes as a host in nature.

MNB: What is the take-home message of your work?

NK: The spiny ants are known to use other ant colonies as hosts as well. These are characteristics that are supported by various levels of evidence, including experiments and field surveys. However, it is impossible to document the entire behavior of spiny ants in nature. As with other parasitic organisms, we believe that the relationship between parasite and host needs to be discussed separately in terms of potential and utility. There are surely species with potential as hosts, even if the relationship cannot occur in nature. That should be the part of the essential function of the parasitic mechanism. In reality, however, research is unlikely to proceed except on the basis of records that occur in nature. We believe that in order to understand the function at the molecular level, it is necessary to grasp even the potential parasitic relationships at the molecular level. Our work is based on such a philosophy and will contribute greatly to future research on the social parasitism.

MNB: What was your motivation for this study?

NK: The first is to create a solid quantitative index of parasitic relationships. There are a number of rules, but we thought that we needed to develop a standard for the quantitative value of how well those rules should be met. Another thing I think we need to do is to scientifically return to the world’s knowledge of the events that have been suggested based only on field surveys and very local descriptions. I think this experience was a good example of how this could be achieved.

MNB: What was the biggest obstacle you had to overcome in this project?

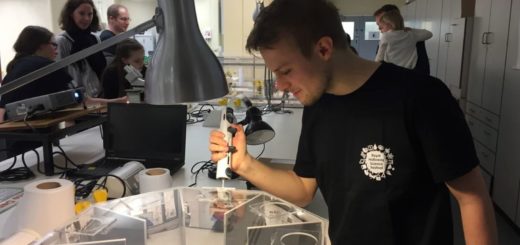

NK: It is not easy to find a colony in a parasitic state from the field on schedule. The impetus for this project came from the dedication of the two first authors (Hironori Iwai and Yu Kurihara, students of graduate school in Keio University), who have been doing field research on a regular basis. Their efforts are the most important point and the core of this paper. Furthermore, accidental discoveries are not enough to make a paper. It was essential to have the knowledge to determine that the discovered colonies were parasitic and to prove it experimentally. In particular, we conducted a great number of behavioral experiments to scientifically prove whether hybridization was due to parasitism.

MNB: Do you have any tips for others who are interested in doing related research?

NK: My team is not only good at ecological approaches, but also at molecular biology and bioinformatics. In the future, there will be many issues in biology that cannot be solved with only one approach, and an interdisciplinary perspective will be essential. Therefore, it is a good idea to take advantage of various opportunities to expand your own areas of expertise and to increase the number of collaborators.

MNB: Where do you see the future for this particular field of ant research?

NK: Many of the findings from field research are reported in local languages and communities, and the information is fragmented. This fragmentation may be unavoidable since many additional experiments are needed to report the findings in scientific papers. However, all of our research has benefited from the accumulation of knowledge reported by past researchers who have spared no effort in their work. I would like to ask those who are working in related fields to send out as many reports as possible to the global community. I believe that this is essential for the development of the field.

Recent Comments