Open wide! What mandibles can teach us about ant evolution

In the recent study “The head anatomy of Protanilla lini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Leptanillinae), with a hypothesis of their mandibular movement” published in Myrmecological News, Richter et al. investigate the head of P. lini, a probable sister group to the remainder of the extant Formicidae, with various methods. The mandibular articulation of P. lini differs from other ants and represents a derived condition. The authors suggest that P. lini is characterized by various apomorphies related to its hypogaeic and specialized predatory lifestyle. Here, Alice Laciny highlights the main points.

A Review by Alice Laciny

Anyone fond of Formicidae will be familiar with the astonishing diversity of ant species – but perhaps less well-known is the plethora of differently shaped mouthparts that come with the vast array of ants’ life histories and taxa known today. From the lightning-fast trap-jaws of Odontomachus or the long pincers of Harpegnathos, to the characteristic “smile” of Leptogenys, or as part of the robust head-shield of a Colobopsis soldier, form and function of ant mandibles provide ample opportunities to study the functional morphology and evolutionary biology of ants. But what did the heads and mouthparts of the first ants look like, how did they work, and how can scientists attempt to reconstruct this formicid “ground plan” by studying ant species alive today?

In their new study recently published in Myrmecological News, Richter et al. provide a detailed description of the head and mandibles of the leptanilline ant species Protanilla lini that may contribute new insights to help answer these important questions.

The subfamily Leptanillinae may be especially important for understanding ant evolution: Together with the species Martialis heureka (subfamily Martialinae), they likely represent the sister group (Leptanillomorpha) of all other extant ants (the “poneroformicine clade”, sensu Borowiec et al. 2019). This makes studies on Leptanillinae, such as P. lini, especially worthwhile and interesting to understand how anatomical forms and functions seen in ants today have developed and changed over time.

Native to Taiwan and Japan, ants of the species P. lini are hard to spot in the wild: their eyeless workers are an inconspicuous light brown and only around three millimetres long. Furthermore, they live in the soil, where they presumably prey on hypogaeic geophilopmorph centipedes, so they are best collected using laborious sifting methods. However, despite their small size and well-hidden lifestyle, these ants are well worth zooming in and having a closer look, as this publication clearly shows.

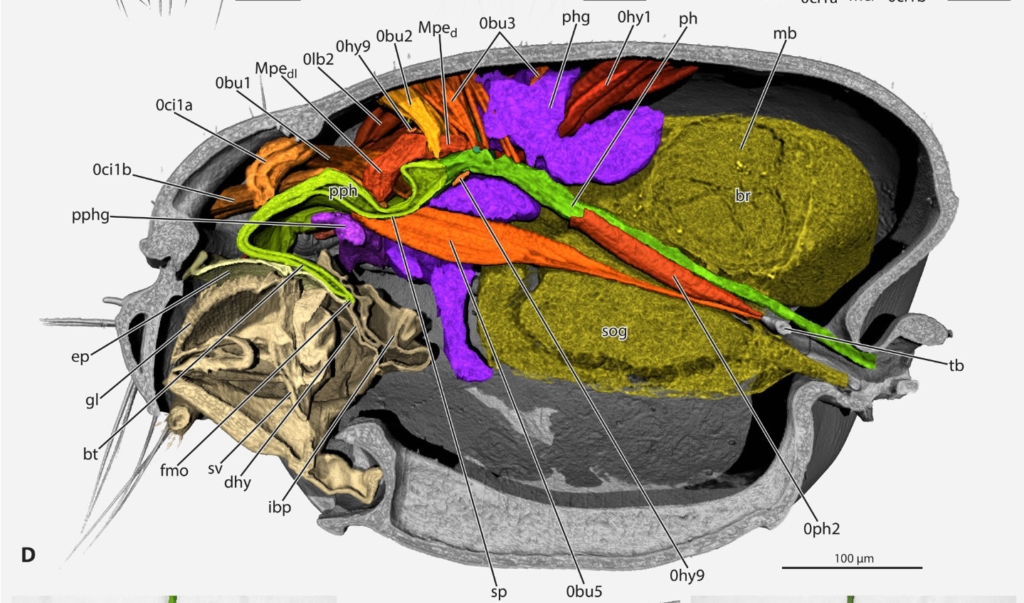

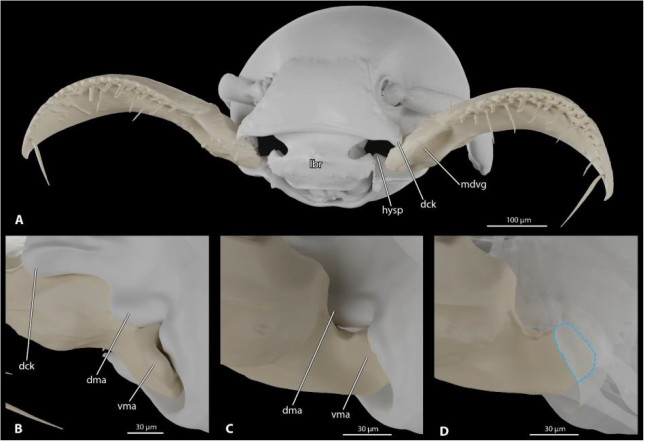

Readers of the paper are in for a treat, as the team of renowned specialists in ant morphology provides intricately detailed descriptions of the internal and external head anatomy of this hitherto rather unstudied ant. To this end, they combined a diverse array of methods including microtomographic scanning and reconstruction, histological sections, light and electron microscopy, morphometry, and even a 3D printed model of the ant’s head. Based on a combination of these approaches, the authors describe the exo- and endoskeletal characters, as well as musculature, gland structures, and elements of the digestive and nervous systems found in the head of the studied species. A particular focus was placed on the anatomy and function of the mandibles, as also illustrated by the 3D model and the supplemental video material.

After presenting the results obtained by cleverly combining this plethora of methods, the authors delve into interpreting their findings in an evolutionary context. Thereby, this paper represents a wonderful example of untangling the mosaic of traits unique to the studied taxon (apomorphic) from those it has in common with other clades, suggesting the presence of the character in a common ancestor (plesiomorphic). Interestingly, very few of the examined characters were interpreted by the team as plesiomorphies of Leptanillomopha relative to the poneroformicine clade, among them the absence of the torular apodeme, an endoskeletal element surrounding the antennal insertion area.

Therefore, despite their phylogenetic placement as the sister group to all other ants, most characters found in Leptanillomorpha are by no means representative of the elusive formicid ground plan. Instead, they are likely linked to the highly specialized lifestyles of these ants as hypogaeic predators: their small size, light and smooth cuticle, reduced eyes, and forward-facing mouthparts and antennae are all ideally suited for a life spent hunting centipedes in tight crevices under the soil. The detailed examinations of mandibular joint architecture and movement in P. lini yielded results that point to a unique morphology and a possible trap-jaw mechanism in the studied species. While this must be confirmed in future studies employing high-speed video observations, the present paper describes an unusually wide mandibular opening angle and the presence of a sophisticated locking mechanism, pointing to the independent evolution of a trap-jaw-like mechanism in this species.

Further studies are needed to finally elucidate the inner workings of Protanilla jaws on the one hand and to find further puzzle pieces of the formicid ground plan on the other. Nevertheless, this study highlights the importance of combining multimodal methodology with a broader knowledge of the life history and ecology of the species under study, in order to make sense of morphological features in an evolutionary context.

Video supplement to the paper, showing mandible movement of Protanilla rafflesi (video by Mark K. L. Wong).

References

Richter, A., Hita Garcia, F., Keller, R.A., Billen, J., Katzke, J., Boudinot, B.E., Economo, E.P. & Beutel, R.G. 2021: The head anatomy of Protanilla lini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Leptanillinae), with a hypothesis of their mandibular movement. – Myrmecological News 31: 85-114.

Borowiec, M.L., Rabeling, C., Brady, S.G., Fisher, B.L., Schultz, T.R. & Ward, P.S. 2019: Compositional heterogeneity and outgroup choice influence the internal phylogeny of the ants. – Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 134: 111-121.

The pagina indication in the reference isn’t correct…

Thank you for pointing this out. We updated the page numbers, which are now correct.

A magnificent article!!!