On the internet, searching for ants leads to new paths to engage with science

In the recent paper “No matter where you are, Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) get attention when it is warm” published in Myrmecological News, Queiroz et al. use Google Trends to infer when and where people google “ants”. Here, Jessie Ebie highlights their main results.

A Review by Jessie Ebie

Ants crawl under the radar of most people until they invade a kitchen, intrude in a garden, or cluster in swarms at a patio light during mating season. If the ants are noticed, their observer often begins a quest to eradicate them rather than investigating the potential benefits that ants bring. This phenomenon is pointed out by Queiroz et al. (2021) in their recent paper. The authors took advantage of the data Google collects on our internet searches to determine when and where there are spikes of interest in ants along with what the most common topics of inquiry are. To do this, authors sourced the data collected in Google Trends (GT) over a period of 13 years in 20 different countries to learn more about when, how often, and why folks searched for the term, “ants.” By including a diversity of countries around the globe, Queiroz et al. (2021) were able to identify patterns that were correlated with latitude while also validating the usefulness and limitations of GT as a tool we can use as scientists to help us better target the general public when sharing our science with them.

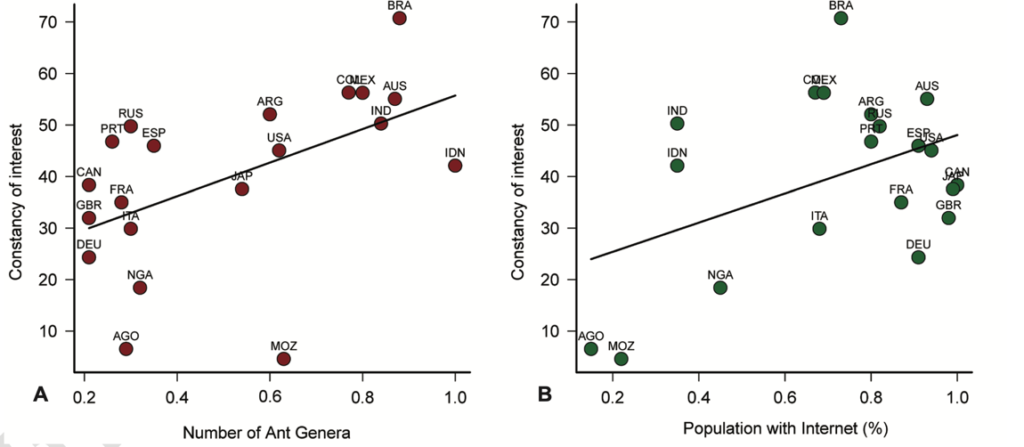

As expected, the authors found a positive relationship between the fraction of a country’s population with Internet access and the number and consistency of searches for the term, “ants,” over the 13-year period of the study (Figure 1B). However, even after controlling for the access to Internet, there remains a significant positive relationship between the number of ant genera in a country and use of the “ants” search term (Figure 1A). It may be that ants are more conspicuous, either due to their number or their contrasts with each other, in countries with more ant biodiversity. Regardless of the causal mechanism, these data show that the interest in a broad taxonomic group like “ants” is idiosyncratic to a country and reflects the unique interest of that country’s people. Furthermore, Queiroz et al. (2021) also saw a general trend of increased interest in warm-weather months in countries in the northern hemisphere or temperate climates that experience seasonal weather changes whereas countries with smaller seasonal variations had a more constant rate of searchers throughout the year. As Queiroz et al. (2021) note, this is most likely because ants become more active during this time making it much more likely that ants will actually invade your picnic basket than during winter months. As most myrmecologists can attest to from experience, people are most interested in controlling ants that enter their space unwelcomed. The results from this study support this anecdotal observation with the majority of internet searches in most countries focusing on controlling ants rather than a general interest in ants or ant-keeping. However, not all countries followed this pattern with some having a larger number of searches related to general curiosity about the ants being encountered. So, again, general interest in organismal biology is tied both to the culture of a country as well as the external drivers that relate to the activity of the organisms under observation.

Queiroz et al.’s (2021) use of the freely available GT data to discern when and why folks around the world are most interested in ants illustrates how scientists can use widely available information to better understand the interests of the general public in their research topics. As the authors suggest, this information can be used to better target public outreach attempts and science communication. Taking this approach would allow us to meet people where they are when they are most interested in the topic. Why not communicate our science to the public when they are already looking for information on the topic? For example, I have seen a recent increase in interest in viruses and vaccine development as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic among my community college students. They are most interested in and ask the most questions about topics when I relate them to COVID-19. I could teach the central dogma in a myriad of ways, but their focus is on the pandemic, and so I utilize this interest to encourage them to learn about the central dogma. It’s much easier to convince someone to engage with a topic when there’s a hook that they are already interested in. Maybe we should consider doing this for more scientific fields. Quieroz et al. (2021) show a perfect example of how we can use readily available data about a very broad audience (much larger than a community college classroom) to better understand the texture of the cross-section of scientific interest across different demographics. The next step is to learn how to utilize this information to better prepare our own public outreach and engagement events so that they leverage current (and possibly fleeting) public interest. After all, we can always start the conversation by talking about ant control and then explain why it might actually be beneficial to have ants in your garden.

References

Queiroz, A.C.M., Wilker, I., Larmar, C.J., Mousinho, E., Ribas, C.R., and van den Berg, E. 2021: “No matter where you are, ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) get attention when it is warm.” Myrmecological News 31: 71–83.

Updated version: Link to publication was added

The pagina indication in the reference isn’t correct…