A journey through ant brains and human genders

Taylor Hart is a PhD student in the Kronauer lab at Rockefeller University. Using transgene insertions, she was able to create clonal raider workers (Ooceraea biroi) that express fluorescent proteins. She uses them to investigate the olfactory receptor neurons which fluoresce during neural activity to locate brain regions responding to specific odors. While she was struggling with some experiments, she was also struggling with her relationship with gender. She realized that she was transgender and non-binary and decided to transition. Here, she shares some impressions of her PhD and her journey.

A View by Taylor Hart

I have always loved biology, with my fascination orbiting around the incredible variety of nature and the scales of biological organization, from molecules to ecosystems. So when I arrived at Rockefeller University for my PhD, totally uncertain where to start, I was drawn to a group of researchers from the Kronauer lab whose interests spanned neurobiology and behavior, collective behavior and physics, ecology, and evolution. They studied ants, not a system I had ever given much consideration to, but I couldn’t discount the lively interdisciplinary dialogue happening around these insects. What’s more, the members of the Kronauer lab were incredibly welcoming and supportive of one another, and I decided to take a leap of faith and pursue a thesis on ants. The supportive environment was key because just as I was anxiously choosing a scientific direction, a second, parallel crisis was brewing within me – more on that later.

In the Kronauer lab, we work with clonal raider ants (Ooceraea biroi). These ants are queenless, with totipotent parthenogenetic workers, and these traits make them relatively easy to control colony composition and also feasible to make genetic modifications. During the first part of my PhD, I developed protocols for transgene insertions in that system, so we can label cell types and use genetically-encoded tools to examine and perturb the ants’ physiology. When my transgenics project finally yielded ants expressing fluorescent proteins, I was extremely gratified to see cell populations outlined in fluorescent emissions from within the bodies of living ants. It feels extremely rare and lucky to have these intimate vantage points on another living thing.

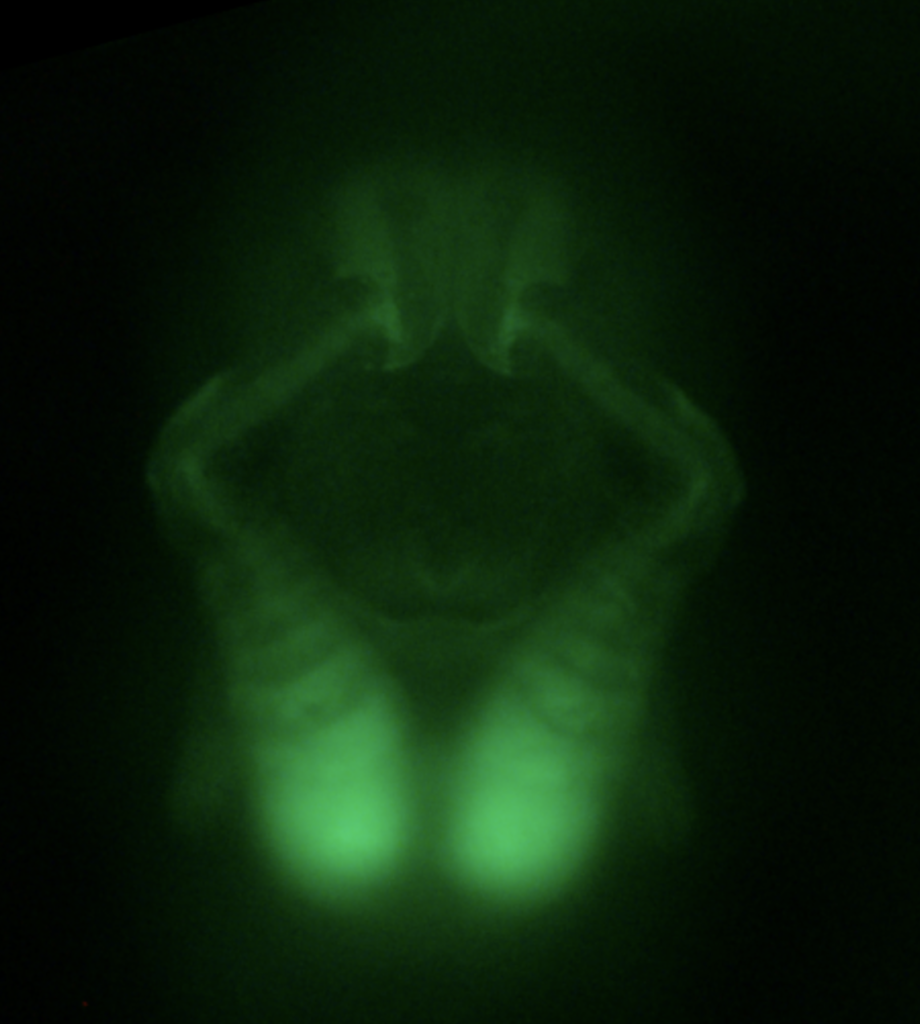

Close-up on a pupa showing expression of a green marker gene in olfactory sensory neurons (© Taylor Hart).

An adult showing a broad expression of a red marker gene (© Taylor Hart).

One of the things I like most about this work is the time I spend staring into ant nests. I find observing creatures going about their business is calming and helps me avoid ruminating too much inside my own head. There is so much to focus on: I have come to appreciate the beauty in thickly-armored bodies, patterns of antennal tapping behaviors, and close-knit societies so different from our own. I am especially captivated by the enormous morphological and behavioral variation both across species and within each individual colony. At an abstract level, this multifaceted diversity reminds me that possibilities for ways of living are expansive, and has given me some comfort when considering my own options in life.

More practically speaking, I’ve put these fluorescent ants to use for tracing individual lineages within otherwise clonal populations. This strategy allows me to track reproductive variation across individuals and over time under very controlled social conditions, and we have already seen some surprising patterns. My other major project is investigating the ant’s sense of smell. We know ants have great olfactory capabilities based on the large number of olfactory receptor genes they possess, the elaborate structure of relevant parts of their brains, and their propensity for pheromone-based communication. In order to study the system in action, I made transgenic ants that express a fluorescent calcium indicator in their olfactory sensory neurons. As a result, these neurons now fluoresce during neural activity, allowing me to find and study the regions that respond to various odors.

I enjoy my work, but the many months of testing a new protocol only for total failure are draining. I’m prone to catastrophizing before mustering the energy to try another set of parameters, and I do sometimes ask myself why I chose a project with quite so much troubleshooting — first with the egg injections, later with the neural imaging. I’m in my 6th year in the program and trying to wrap it up, but it is extremely gratifying to finally be able to see the neural basis of smell in action. I think it’s going to be fantastically interesting to learn more about the development, function, and variation within the olfactory system in ants. Beyond my lab work, I try to maintain smaller victories through side projects, working with Rockefeller’s LGBT+ organization, PRISM, and doing outreach and teaching with Rockefeller’s RockEdu program. I feel especially lucky that I’ve been able to incorporate my research on ants into programming for local high schoolers with RockEdu.

A parallel question

Back near the start of my graduate studies, at the same time as I was pondering the intellectual, personal, and professional possibilities that would open for or close for me depending on my chosen thesis topic, a parallel question separate from my science came to loom large on my mind. I began questioning my gender. Of this much I was certain: despite having been assigned the role as such, I was not a man and would not be able to perform that part for much longer: I am transgender (or just trans). At the same time, I could not definitively place my internal sense of gender within the traditional binary of man/woman, or even tell for sure if I had an internal sense of gender. For that reason, I am also non-binary.

From that point on, while I tried to make progress on my studies, I was also trying to study myself. I became acutely aware of how my habits and dress, my bodily characteristics, and the place in society I occupied were produced by many forces. Some of these I could influence, but what combinations would bring me comfort and happiness? The question was overwhelming and destabilizing: while I can run ant studies with many replicates and control groups to infer causality, I was just one person. I wanted to approach this critical topic scientifically, but all I could do was try things and see how they felt.

Over the years I tried on ranges of dress and behavior from androgynous to quite feminine, and learned that expressing femininity feels good. One of my most revealing experiments was going on feminizing hormone replacement therapy, which has greatly reduced my general anxiety and brought me much better comfort with my body. I cannot know how other versions of me would feel about their life, but the choices I have made have calmed my need for definitive answers. During the last year, I have begun being treated as a woman in day-to-day life, and I feel comfortable settled into this role for the time being.

For most trans and non-binary people, gender is an intense and highly personal framework for self-understanding and expression, which we engage with despite our upbringing, the roles assigned to us by society, and the normative systems imposed by state and private institutions. We reimagine existing gender terms and create new ones to suit our needs, always with the understanding that labels cannot capture the nuances of experiences. Regardless of the words used, all genders and expressions of gender are worthy of respect and support, and we must work to disassemble systems that coerce people’s genders.

The simplest, most minimal part of supporting trans and non-binary people is to treat us with respect by referring to us correctly. This means always using our chosen names, pronouns, and appropriately-gendered words when talking about us.

I feared coming out for more than three years after I knew I was trans because I expected to become unintelligible to the people and the institutions that shape my life. But, I found that enacting my transition has been straightforward, buffered by my position in mostly white, educated, middle-class society. This is far from the norm. Many of my trans and non-binary siblings face discrimination in housing, employment, and healthcare (both general forms of care as well as accessing life-saving hormones and surgeries if we choose), as well as harassment and violence. Legal and institutional protections against these forms of oppression are scattered and incomplete across the US, facing reversal in places like the UK and eastern Europe, and absent in many parts of the world. We are variously denounced as deceptive abusers or deluded self-harming victims, none of which is supported by science. Rather, we are a small but diverse group of people who are poorly understood and in need of care and respect.

Academia has a role to play in supporting trans and non-binary people. We need advocates who will continue to push for better protection and access to care within elite circles and policy frameworks. While we are rare in the upper levels of the academy, there are many up-and-coming-trans and non-binary researchers whose voices must be amplified. At the same time, science will benefit from our presence: for instance, planning and enacting my medical transition required developing an intimate understanding of how genetic, developmental, physiological, and environmental factors can be woven together in various complementary and contradictory ways to shape phenotypes. These experiences deepened my practice of biology. Similarly, rebuilding my sense of self has helped me reflect on the construction and usage of taxonomies and ontologies which are critical across disciplines. And of course, we are just good scientists who deserve places in our fields of study. I hope that my work and visibility will help to make more space for us in the future.

Taylor (© Taylor Hart).

Recent Comments