Book review: “Ants”

A Book Review by Aaron M. Ellison

Edited by Alice Laciny and Salvatore Brunetti

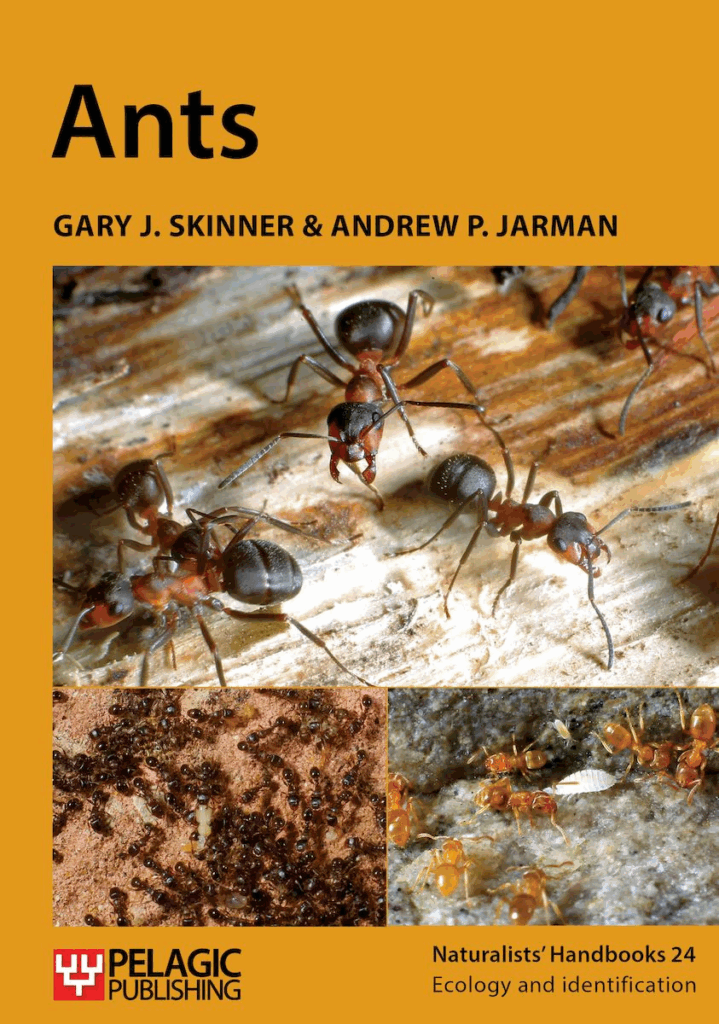

The second edition of “Ants” has recently been released by Pelagic Publishing. According to authors Skinner & Jarman “Ants are among the most familiar of insects and can form a crucial part of their ecosystem, having an impact far greater than their small individual size would lead us to expect. This book is for anyone wanting to learn more about these endlessly interesting insects.” Here, Aaron M. Ellison reviews the new publication, highlights changes from the first edition, and shares his personal insights and views.

“Ants” is a thoroughly revised and greatly expanded second edition of its 1996 namesake, both of which are, perhaps confusingly, assigned number 24 in the respected Naturalists’ Handbooks series now published by Pelagic Publishing. For this new edition (henceforth “Ants” 2e), Andrew Jarman has replaced Geoffrey Allen as Skinner’s co-author, and Jarman is credited with preparation of the new—and apparently well-tested—keys. The book is replete with photographs from the field and lab, most by the authors but some by well-known (and appropriately credited) friends and colleagues. Curiously, however, Sophie Allington, who shared the title page of the first edition and created many of the line drawings that are re-used in 2e, no longer receives credit.

Unlike similarly titled books with a global reach (Bert Hölldobler and E. O. Wilson’s classic, “The Ants”), “Ants” 2e, like other Naturalists’ Handbooks, covers the biology, ecology, and identification of a particular group of species in the “British Isles”, which here refers to Great Britain, Ireland, and the Channel Islands. Of the > 14,000 described extant species of ants, “Ants” 2e includes distribution maps and photographs of the 61 native or introduced and well-established species in the British Isles. This new edition will serve as a welcome, unifying resource for amateur and professional myrmecologists in Ireland and the UK, but unfortunately, some of the best features of the first edition are no longer in evidence.

Weighing in at more than 300 pages, “Ants” 2e is over four times as long as its predecessor. In addition to an expanded introduction and more detailed presentation of the general biology of ants (chapter 2), revised keys (chapter 6), more pointers to myrmecological resources (chapter 8) providing aids to their study (chapter 7), and up-to-date references (chapter 9), “Ants” 2e includes whole new chapters on distribution and abundance (chapter 4) and conservation and management (chapter 5). Chapter 2 of the first edition has been split into a more comprehensive discussion of ant biology (chapter 2 in 2e) and a new chapter on ants and their environment (chapter 3). The former covers nests and nest construction, reproduction and the ant lifecycle, foraging and feeding, and castes and the division of labor. The latter covers ant communities and biotic interactions with a wide range of other organisms—plants, myrmecophiles, predators, and parasites—along with guest ants, thief ants, inquilines, and cleptotectons (sensu Breed 2020; it is surprising that Skinner and Jarman continue to use the more fraught term “slave-maker” in their discussion of Formica sanguinea, although the linguistic battles over myrmecological terms remain unresolved. See Olson & al. 2019 and Herbers 2020 for opposing points of view, and Ellison & Gotelli 2021 for a review). In contrast, ants’ interactions with their abiotic environment (only soil in 2e) are given comparatively short shrift (a scant page-and-a-half in a 29-page chapter). All the chapters are well-written and expansively illustrated with photographs, figures, and tables; reflective of the current technical literature; and full of useful information for anyone learning about or studying ants.

The new chapter 4 on distribution and abundance of the British and Irish ants accounts for over 40% of “Ants” 2e. The information contained in this chapter, however, simply does not justify the space consumed. Each species gets a two-page spread. A short paragraph about the species together with summary lines describing its size and flight period occupies the top half of the verso (left) page in the spread; the bottom half contains a photograph of the dorsal view of a museum specimen that presumably had been glued to a small card (the mounting method preferred by Skinner & Jarman; see chapter 7). As Skinner & Jarman correctly note, these photographs “are not intended to be illustrative of identification features” needed to use the keys but rather provide only an overall visual check once an identification is made. Because anyone looking at an ant in the field while holding it between thumb and forefinger is likely to be looking at the ant in profile, dorsal photographs will not be as useful as profiles for such visual checks. Further, many of the photographed specimens are contorted and missing legs or antennae, which reduces the aesthetic appeal of these magnificent creatures. The recto page gets a full-page map of Britain and Ireland with symbols indicating locations of collection records shaded by decade (since 1994) of their collection. Similarly detailed maps elsewhere in the book (e.g., the unexpectedly duplicated Figures 1.7 and 4.2) take up only half a page, so it is not clear why each entry in chapter 4 could not have been generously fit on a single page. Finally, the species are presented alphabetically by genus (and not within subfamily), which represents a missed opportunity for incorporating evolutionary information into this chapter.

The real value of the book for amateurs and professionals alike is in the keys (chapter 6). Jarman has produced new, detailed, and up-to-date species-level keys to workers, queens, and male, as well as separate field keys (as flow charts) to the 23 most common species and the distinctive nests of 13 of them. Of course, most of the taxonomic characters are visible only in profile or face views, and the absence of Geoffrey Allen’s beautiful colored and monochrome plates of profiles of workers, queens, and wings that graced “Ants” 1e and that added comparative fine details to go with its keys is not at all made up for by the photographs in chapter 4 of “Ants” 2e. It also is not clear why the keys follow, rather than precede, the long chapter on distribution and abundance. If the latter are indeed useful only after an identification has been made, chapter 6 ought to precede chapter 4.

The penultimate chapter on studying ants (chapter 7) is a welcome expansion of the “techniques” chapter of the first edition. Here, the photographs of field collecting methods, cases of specimens, and nest boxes are really helpful. I was surprised, however, that after the thoughtful discussion of conservation and management of ants in chapter 5, which includes nine threatened or vulnerable species with Biodiversity Action Plans and four red wood ants (Formica rufa-group species), there was no discussion of potential negative impacts of collecting such taxa. It is certainly true that hand-collecting only one or a few workers will have little impact on a colony or a population. On the other hand, queens and males are often collected in pitfall traps and the other bulk collection methods illustrated (sweep nets, curtains and beat sheets, sieving leaf litter, tiles, and especially Malaise traps). Collecting and killing reproductive ants can lead to the death of an entire colony and should not be encouraged.

It’s important that we all share the knowledge we gain through studying ants and other species. So, I really appreciated the closing paragraph where Skinner & Jarman strongly encourage the submission of new observation or collection records to the Bees, Wasps, and Ants Recording Society (BWARS: https://www.bwars.com), iRecord (https://www.brc.ac.uk/irecord), or local environmental records centres (https://www.alerc.org.uk). I would add iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org/) to that mix if good photographs of sample records also are available. And last, Skinner & Jarman encourage myrmecologists of all stripes to publish their findings so others can learn more about ants—as, indeed, Skinner & Jarman have done very well in “Ants” 2e.

References:

Breed, M.D. 2020: The importance of words: revising the social insect lexicon. – Insectes Sociaux 67: 459-461.

Ellison, A.M. & Gotelli, N.J. 2021: Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and humans: from inspiration and metaphor to 21st-century symbiont. – Myrmecological News 31: 225-240.

Herbers, J.M. 2020: Racist words in science. – BioScience 70: 946.

Hölldobler, B. & E.O. Wilson. 1990: The Ants. – Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA, 732pp.

Olson, M.E., Arroyo-Santos, A. & Vergara-Silva, F. 2019: A user’s guide to metaphors in ecology and evolution. – Trends in Ecology & Evolution 34: 605-615.

Recent Comments