Ants, Plants, and Predatory Behavior: An interview with Alain Dejean

Alain Dejean, has dedicated his career to studying ants, especially focusing on their predatory behavior, their venom and interaction with plants. For his work he visited many tropical countries and collaborated with Edward O. Wilson and Jérôme Orivel. In this interview we asked him about his recent review paper on predatory ant foraging.

An Interview compiled by Salvatore Brunetti and edited by Elia Guariento.

MNB: Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

AD: I am now almost 80-years old, an old timer. I believe that, although it was not my wish as I preferred to have a position of assistant professor just after defending my first dissertation in 1974 (in French: Thèse de spécialité), I was very lucky as I got a job in East Africa via the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Thus, during six years I taught Human Biology to students in their first year of medicine, leaving me free to conduct my research. Because my wish was to organize a study on the predatory behavior of ants, my dissertation adviser, Professor Luc Passera, contacted Edward O. Wilson in order to define a subject. In his very rapid response, E.O. Wilson suggested I look for Dacetine ants specialized in the capture of collembolans; if possible, to also look for other ants morphologically adapted to predation, such as Odontomachus. So, during six years I worked on these ants, which permitted me to defend my second dissertation (Thèse d’état) in 1982. Still with the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I worked in Zaïre (now The Democratic Republic of the Congo) during three years, always on the same subject but with more “practical” applications. The third year I obtained a permanent position as assistant professor in the University Paris XIII, but still paid by the French Foreign Affairs for a two-year study in Quintana Roo, Mexico. To work in the Neotropics was a true revelation as I realized that the notion of plate tectonics does not only apply to geology, but also to ant biology at all levels, including ant-plant relationships, so that I worked almost day and night every day during two years in order to have publishable results. Indeed, I was rapidly informed that I was going to be appointed to the Laboratory of Zoology of the University of Yaoundé, Cameroon, whose director was Professor Jean-Louis Amiet. There, I benefited from both his friendship and his long experience, and was truly able to understand how ants and plants coevolved on both sides of the Atlantic. Indeed, I suggested to Jean-Yves Collet, a film producer, to make a movie whose title was “L’arbre et les fourmis” (later presented by the Discovery Channel as “The tree and the ants”). Also, it was from Yaoundé that I began a series of missions in French Guiana with Bruno Corbara under a project organized by the botanist Monique Belin, so on the other side of the Atlantic.

In September 1993, I obtained a teaching position at the University Paris XIII. There, too, I benefited from the friendships and experience of my colleagues, particularly Alain Lenoir who had come several times to Yaoundé. Then, I became a professor at the University of Toulouse III. In both cases, I conducted a series of three to four missions per year in Petit Saut, French Guiana, still working on predatory ants and ant-plant relationships. I then spent six years (2005 to 2010) as a researcher in French Guiana, with the French CNRS (National Center for Scientific Research).

This allowed me to participate in nine other movies, and, thanks to the French entity Radeau des Cimes (Canopy Raft) led by the botanist Professor Francis Hallé, Bruno Corbara, Jérôme Orivel and myself participated in a series of missions in Cameroon (1991), French Guiana (1996), Gabon (1998), Madagascar (2001) and Panama (2003) mostly to study canopy ants.

MNB: Could you tell us about your area of research?

AD: For my first dissertation in 1974 (Thèse de spécialité), I studied the reproductive behavior of Temnothorax in France using a Cobalt 60 irradiator to selectively castrate queens or workers. Then, in January 1975 I began to study the predatory behavior of ants with an evolutionary approach based on the Red queen theory by Leigh Van Valen (1973, Evolutionary theory 1: 1-30). In fact, whether the ants are ground-dwelling, arboreal, or mutualists of myrmecophytes, I still use this approach.

Later, in reality via the work of Jérôme Orivel, now director of research in the French CNRS, I organized research studies on ant venoms, studies that are ongoing thanks to Jérôme and Axel Touchard.

As a result, we published several research papers for which I suggest looking on ResearchGate as I have not taken a precise listing.

MNB: Could you briefly outline your research on “Foraging by predatory ants: A review” published in Insect Science in layman’s terms?

AD: Based on information gathered from the literature, we examine how different ant species organize their search for prey.

In fact, this study is the first part of a work dealing with the predatory behavior of ants (the second part is now ready to be submitted).

MNB: What is the take-home message of your work?

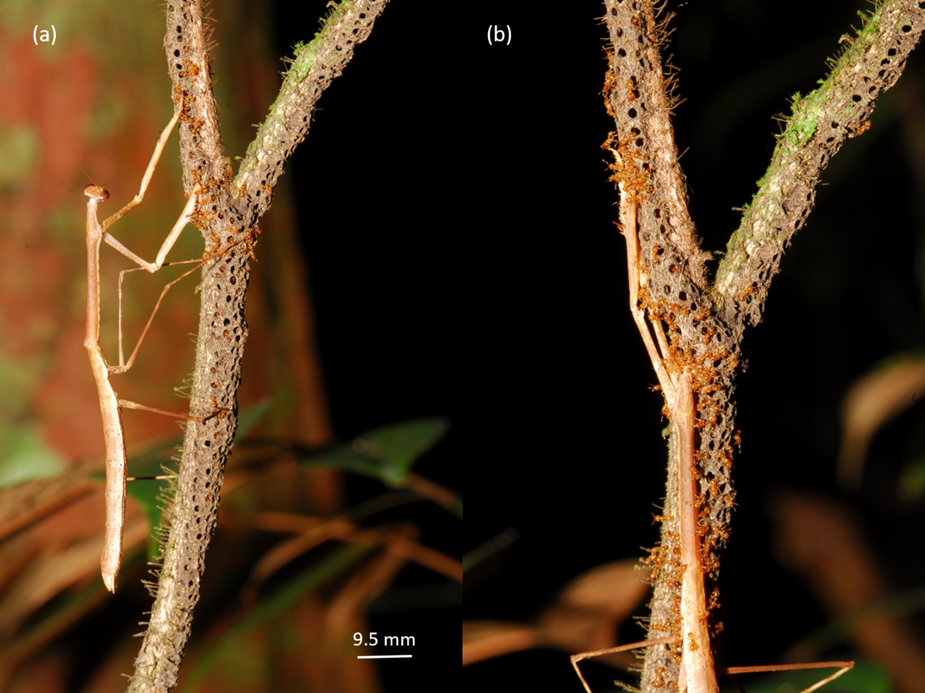

AD: Over the course of evolution, ants have developed very different means of prey capture, including arboreal species using fungus to reinforce gallery-shaped traps.

MNB: What was your motivation for this study?

AD: This was the result of years (1975-2019) of studies, plus, of course, the results published by several researchers on this topic.

MNB: What was the biggest obstacle you had to overcome in this project?

AD: None.

MNB: Do you have any tips for others who are interested in doing related research?

AD: I believe that there are enough researchers working on predation by ants in the Neotropics, but it is likely that new discoveries are possible from Myamar to Indonesia, in the Philippines, New Guinea and northern Australia, plus the Pacific islands.

MNB: Where do you see the future for this particular field of ant research?

AD: Likely the response is above.

MNB: Thank you!

Recent Comments