Interview with Philip S.Ward

Phil Ward is a myrmecologist and professor of entomology at the University of California, Davis. His extremely prolific work on ant systematics and phylogeny has been and continues to be highly influential for many of us in the myrmecological world. In this interview, we talk about his many different research projects, his conversion from lepidopterologist to myrmecologist, and the perils and merits of morphological and molecular methods.

An Interview compiled by Alice Laciny

MNB: As an introduction, could you please tell us a bit about yourself and your current position?

PSW: My name is Philip Ward, you can call me Phil, I’m a professor of entomology at the University of California, Davis, in the Department of Entomology and Nematology, and I pursue research on ant systematics and evolution.

MNB: Great! And what are your main research topics or any current projects you are working on?

PSW: Oh, always too many (laughs)! Well, fundamentally I am working in different areas of ant systematics, including both species-level taxonomy and molecular phylogenetics of selected groups of ants. I have many projects going – possibly too many. I am working on various taxa of the subfamily Pseudomyrmecinae, I’m interested in the phylogeny of the tribe Camponotini – we just got a new grant to study that – I’m working with Jack Longino to study the ants of Central America, and I have ongoing interest in other groups as well, like Nearctic Crematogaster… There are just so many projects bubbling, some more center-stage than others.

MNB: Wow, fascinating, that’s really quite a lot! So, to give us some comparison of where researchers come from and where they ended up, what was your beginning in myrmecology like? Were there any topics or people that inspired you to get into ants?

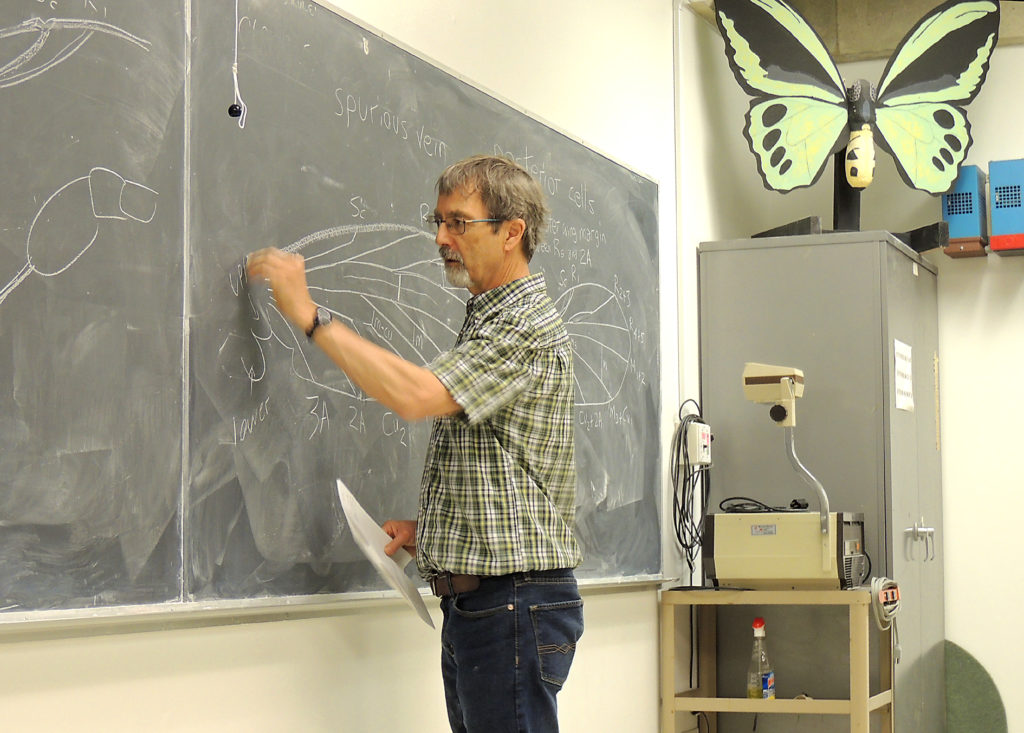

PSW: Yes, absolutely. I was an undergraduate student in Canada, I studied population biology, and my study organisms were actually Lepidoptera: I studied their community dynamics. And then, in my third or fourth year, my life was changed by several things: One was reading E. O. Wilson’s book “The Insect Societies” – it was an inspiring experience to read that and to appreciate how fascinating are the life histories and evolution of ants. I sort of realized that Lepidoptera are pretty, but ants are really fascinating! I switched my research interests as an undergrad from lepidopteran communities to ant diversity and evolution. I was also influenced by W.D. Hamilton’s papers on kin selection and the enthusiasm of my fellow undergraduate students, people like Adrian Forsyth and Chris Darling. So, a confluence of events and factors got me highly interested in ants and I decided to pursue my PhD in Australia, which I knew had a very rich ant fauna.

MNB: Great to see you have stuck with ants until now!

PSW: Yes, there was no turning back! Many years later I had the opportunity to meet E. O. Wilson and thank him personally because his book changed my life! Such accessible prose and a delightful style… that basically put me on this path for the rest of my life.

MNB: That’s wonderful! And if you compare that early phase to your scientific life today, how have your motivation and methodology changed?

PSW: Back then, when I was a graduate student, I was a “gel jockey”, so I was enamored with the use of gel electrophoresis to generate genetic markers to study colony structure in ants. That was my modus operandi during my PhD, when I was studying the Australian genus Rhytidoponera. I then gradually left behind questions about social behavior, kin selection, and population genetics, and focused more on systematics and phylogeny. During those years, I abandoned molecular methods and became a morphological taxonomist for a couple of decades. And then, in the early 21st century, I began adopting molecular methods again after this period of just doing strict morphology. I began to appreciate the power of molecular markers for ant systematics and taxonomy, rather than for population genetics. I utilized Sanger-sequencing PCR methods to generate markers to study the boundaries of species and the relationships of species to each other. I used that technique for a couple of decades and just recently in my lab, we have been transitioning to phylogenomic approaches, where we are looking at thousands of genes instead of 10 or 12. That is incredibly informative and provides even more detailed, resolved phylogenies than we had before. But I have not abandoned my morphological roots, I still spend a lot of time at the microscope looking at ants. I’m still a firm believer in the virtues of using morphological information to delimit species and to provide information about phylogenies. In fact, systematics covers several areas: one is species-level taxonomy and at that level, I think we will always depend on morphology for identifying most species. In terms of generating phylogenies, however, molecular markers are far superior. I’ve made mistakes in the past by inferring phylogenies with morphology only, which later turned out to be wrong. It’s a humbling and liberating experience! So now I think that genetic data is the most suitable way to generate well-resolved phylogenies, but having done that, we need to diagnose and distinguish our taxa with morphological information, if nothing else for purely pragmatic reasons.

MNB: Right, both sets of methods are certainly important! So, if you could look into the future, what would your prognosis for the development of myrmecology over the next 10 years be?

PSW: Myrmecology, of course, is a huge area, much larger than what I do, which is primarily systematics and phylogeny… In the field as a whole, I think we can expect great advances and new methods in the study of ant ecology and behavior, and social organization. In my own area, it’s clear that we will continue to expand our progress using molecular methods to improve ant phylogenies. And there will be lots of exciting downstream analyses and applications of those phylogenies to answer broader evolutionary questions, such as we see coming out of the labs of people like Evan Economo and Corrie Moreau. That will certainly continue, and we can expect lots of exciting findings. One area in which I hope to see more progress (but I’m not completely sanguine about it) is alpha taxonomy. There is still a tremendous need for high-quality work on the species-level taxonomy of ants and I do hope we will see advances in that area, too. One way that could happen would be through a stronger marriage between molecular and morphological methods, like the more sophisticated application of molecular data for species delimitation. Perhaps we could sequence all the specimens in our collection from single legs and generate terabytes of genomic data… but would we want to do that? As a taxonomist working with insects, I examine thousands of specimens, and I suspect that there will always be a need to sort and determine specimens based on morphology. But that is an open question… species-level taxonomy is the area of myrmecology where I think we most need progress to be made.

MNB: We certainly need a combination and integration of approaches to get there – marriage is a good analogy! What would you do differently if you could start all over again? Was there ever a plan B for your career?

PSW: Well, when I was a young undergrad, I thought I might just become a hippie and live in a commune (laughs)… but that didn’t eventuate. Later, as I began to look at the world of Hymenoptera, I thought about studying gall insects because they have fascinating biologies as well. And of course I could have stuck with Lepidoptera. I was really enamored with butterflies and moths from when I was six or seven years old until I underwent this “conversion”. As an undergrad, I was really interested in lepidopteran taxonomy, diversity, and ecology, so I could have conceivably returned to my roots. So there are three alternate-universe scenarios for you! (laughs)

MNB: Those are great! So, is there any favorite anecdote you can tell us from your research life –something scary or funny perhaps?

PSW: Well, things that are funny are often only amusing in retrospect… When I was a graduate student, I worked in a lab at the University of Sydney, upstairs on the third floor. I frequently had to fill up carboys with distilled water to do my electrophoresis work. One time, at the end of the week, I must have left a spigot open and realized on Monday morning that I had basically flooded the lab! Even worse, on the second floor, below the lab, was the office of my major professor, Charles Birch. The water had leaked through the floor, shorted out several lights in his office and spilled onto his desk! Needless to say, he was not amused! It seems funny now, but at the time I was horrified! (laughs)

MNB: Oh no, that sounds bad! Luckily you got to keep your job!

MNB: On a slightly more serious note – here in Austria, we are still noticing that despite high enrolment numbers of female biology students, you find fewer females the higher you look on the career ladder, e.g., as professors or museum directors. This is probably similar in the US. What’s the situation like in your lab? Any ideas on how to tackle this issue?

PSW: Of course, as you say, it’s all well and good to bring in more female students, but we are losing them, there is this “leaky pipeline” – a rather terrible metaphor used here in the US. So we have to alter the structure of institutions to make it more appealing for women and minorities to stay in this academic world. It’s not a bed of roses being an academic, there are many difficulties, high pressure, finding work-life balance and so forth… So we have to think about new models for the workplace that make it more encouraging for people to stay in academia. In my undergraduate classes, I see a huge sea of wonderful diversity – women, people of color, a plurality of viewpoints. But the problem is that these people are not staying for the longer haul. So we need to make structural changes to institutions to make them more inviting. In terms of access to childcare and other family resources, while being able to continue your career, for example, Europe is ahead of the US.

MNB: Right, child care is often a main factor. So, do you have any suggestions for early-career myrmecologists of all genders on how to find your place in the myrmecology world and how to stay in?

PSW: Every individual is different, of course, so this is just very general advice… But a key thing is to be passionate about your interests so that studying ants is not just a job but a hobby that you amazingly get to be paid for! That’s the most delightful thing if you do it because you love exploring the world of ants and nature! That’s the right attitude to adopt, I think. In terms of approach to research, I’m in my own particular field of systematics and don’t want to prescribe anything for other fields, but an important thing is to act locally and think globally. So, while focusing on your own detailed topic in a particular space and time, think of it in the global context of the evolution of ants. There’s a danger of getting too parochial sometimes, so always keep that broader temporal and spatial scale in mind!

MNB: Thank you for this great advice!

MNB: Is there one single thing you wish everybody knew about ants?

PSW: I wish society appreciated the overwhelming diversity of ants. People will often treat ants as a generic thing, like “the lab rat”, but ants are so incredibly diverse and that’s an important take-home message.

MNB: Definitely! And is there a commonly asked question you get very often?

PSW: Of course, and I’m sure you get this too, the general public will ask how to get rid of ants in their kitchen. Here in California we have a particularly pernicious introduced species, the Argentine ant Linepithema humile, which has invaded most urban areas of the state. And it really is a horrible ant – one of the few I dislike (laughs). But even watching Argentine ants can be an informative experience! So I would like people to appreciate that these ants are just a nuisance, not a major hazard to our health, and to take a more philosophical approach to ant invasions.

MNB: But is there actually a way to get rid of them?

PSW: (laughs) I have very few ants in my own house, they must know I’m a myrmecologist! I do know that, for the control of Argentine ants, poison baits work fairly well. I have colleagues working to limit these ants on islands off the coast of California because they threaten the native fauna, and they have been quite successful using such baits.

MNB: Ok, good to know!

MNB: Do you have a favorite morphological structure or phenomenon related to ants?

PSW: When I look at ants under the microscope I’m looking at them holistically, so I don’t focus on any single part. Some of my students have done amazing work on particular parts, like Brendon Boudinot’s studies on genitalia. But I’m more enamored with the entire phenotype!

MNB: Very nice! Now just some very quick questions: What’s the book on your bedside table?

PSW: I just finished reading Primo Levi’s “The Reawakening”, an account of his time after he left Auschwitz and returned to Italy. A wonderful, moving book.

MNB: Watching or doing sports?

PSW: Well… neither.

MNB: Listening to or making music?

PSW: Listening, though I would love to make music.

MNB: Evening or morning?

PSW: Morning.

MNB: Tea or coffee?

PSW: Tea, please!

MNB: Sugar or sweetener?

PSW: Sugar.

MNB: Cooking yourself or eating what someone else cooked?

PSW: I like to cook!

MNB: Habit or change?

PSW: I’m a creature of habit, but I appreciate change.

MNB: Aspirator or forceps?

PSW: Aspirator.

MNB: Nest densities or pitfall traps?

PSW: Nest density.

MNB: Field or lab?

PSW: Field.

MNB: Pin or ethanol?

PSW: Pin… actually, point-mounted!

MNB: Paper reprint or PDF?

PSW: PDF.

MNB: Journals financed by the author (open access) or the reader (subscription)?

PSW: Open access, that’s an easy one.

MNB: Kin selection or group selection?

PSW: Kin selection.

MNB: Monodomy or supercoloniality?

PSW: Supercolonies are fascinating!

MNB: Worker or queen?

PSW: Worker.

MNB: Your favorite ant?

PSW: Hmm… impossible question! One of my favorites is Opisthopsis.

MNB: Great! Thank you so much for the interview!

References

Ward, P.S., Blaimer, B.B. & Fisher, B.F. 2016: A revised phylogenetic classification of the ant subfamily Formicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with resurrection of the genera Colobopsis and Dinomyrmex.” – Zootaxa 4072.3: 343-357.

Lenoir, A., Boulay, R., Dejean, A., Touchard, A. & Cuvillier-Hot, V. 2016: Phthalate Pollution in an Amazonian Rainforest. – Environmental Science and Pollution Research 23: 16865-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7141-z.

Wonderful interview