Interview with Sylvia Cremer

Sylvia Cremer is

An Interview compiled by Alice Laciny

MNB: We always like to start off with a short introduction, so could you please tell us a bit about yourself, your position and your current research?

SC: I’ve been here at the IST Austria since the end of 2010, when I started as an assistant professor. Since 2015, I have been a full professor, so I have a group of about ten people here, and we work on social immunity in ants. I did my PhD in Regensburg with Jürgen Heinze, then a postdoc in Copenhagen with Koos Boomsma, and then I spent a few months as a junior fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg in Berlin, at the Institute of Advanced Sciences in the evolutionary immunology focus group. That’s basically where I combined the social insect world, which I had been working with since my PhD, with disease and host-pathogen interactions into the field of social immunity, which I pursued from then on. Then I became a group leader in my habilitation position at the University of Regensburg – and then I came here!

MNB: That’s quite an impressive career!

SC: A very European one.

MNB: True, unusually European! Could you please explain the concept of social immunity in a few sentences, for any readers who might not be familiar with the topic?

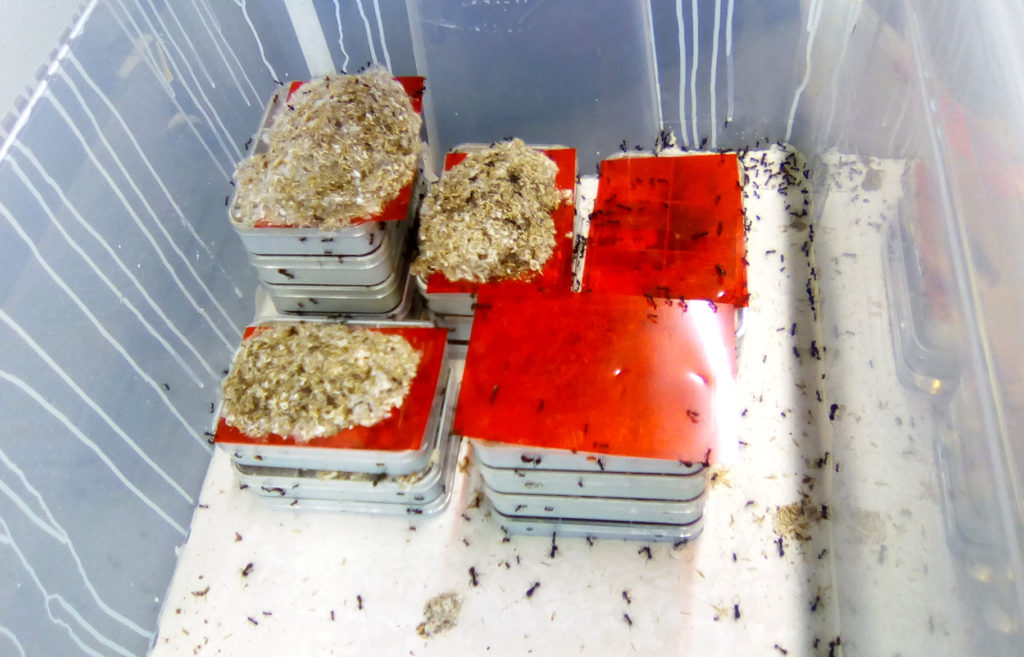

SC: We study the cooperative disease defenses of social insects using the model organism of ants. In these superorganisms, we find that the whole colony is actually defending itself against diseases. At different stages of a disease progression, ants perform different types of defenses. I think the best analogy to draw is between this and organismal immunity – for example, in your own body each individual cell has cell-autonomous immunity, but in addition, some somatic cells have evolved into an immune system which acts in the whole body. And in social insects, we have the same scenario – each individual has an individual immune system as well as behavioural defenses, like avoidance. But in addition, the collective cooperative actions of the workers cause this additional level of social immunity to protect the whole colony.

MNB: So this is also where the concept of the superorganism ties into it?

SC: Yes, exactly. The superorganismal view states that the colony – like a body – is also separated into a germline – the reproductive queen and the males – and the somatic tissue, which is the sterile workers. These two are dependent on one another for reproduction, and selection acts at the level of this reproductive unit. At this cooperative level, we look at how disease defense is organized.

MNB: Great explanation, thank you! So if we move on from your current research and look into the past, what was your beginning in myrmecology like? Was there something or someone in particular that inspired you to get into ants?

SC: I got into ants with my PhD supervisor Jürgen Heinze, but I already had some interest in the topic during my master’s. I also had the nice opportunity to attend a series of regular meetings on social insects – a European training network coordinated mostly by Copenhagen. It consisted of around ten European research groups working on social insects and the PhD students gathered about twice a year, so it was a very strong community, which I found very cool. Then Jürgen offered me a PhD position, and I really liked the topic. In my time, you mostly heard about cooperation and the good of the colony, but what I found interesting was the combination of conflict and cooperation in these societies. So my PhD was on male fighting and male dimorphism in Cardiocondyla ants. In the beginning, I was working on the ants themselves, then in my postdoc I continued with invasive ants – Lasius neglectus as a new invasive species in Central Europe. I found the supercoloniality really interesting, this “supercooperation” across nests. Then, during my postdoc in Copenhagen, quite a few people were interested in host-pathogen interactions. This was also related to my topic, because the success of invasive species can be explained by the release from parasites and the lack of adapted pathogens in the new habitat. So this was my entry into the host-pathogen topic in social insects. And then during the Wissenschaftskolleg, I really tried to dig into what we now call social immunity.

MNB: Wonderful! This also ties into the next question – what is your motivation now? Why are you still working on social immunity? And how would you say your methodology has evolved?

SC: I think it’s a fascinating topic, which I have been working on for 12 years now. And we can still describe novel behaviours, even after looking at the ants for more than a decade! So there’s still a lot to discover. We also have other methods available now, and we ask different questions. I started working as a behavioural ecologist, so I did behavioural observations and tried to find interesting experimental setups to find out what would cause conflict or cooperation. But now, we have other tools integrated into our research: we can do social network analysis, use automatized tracking programs… So now I would say I am an evolutionary immunologist, a network analyst, a chemical ecologist, a molecular biologist… We kept more or less the same questions, but we broadened our spectrum of methods, which, in turn, leads to more detailed questions you can ask. In the beginning of my social immunity work, I was interested in what the ants were doing in a one-on-one interaction – how they clean each other, how they include antibiotic treatments or remove infectious particles. Now, I am focusing more on the colony level to see how these different behaviours are integrated to form a systemic, colony-wide response and how this affects the fitness.

MNB: That also sounds like very interdisciplinary work, right?

SC: Yes, we use a lot of different methods, which also leads to very nice collaborative work with specialists, like chemical ecologists, to get help with more specialized problems. We’ve also worked with theorists to model some problems we cannot directly address in the lab, which is also an interesting thought experiment.

MNB: That sounds great! So, if you try to take a look into the future, how do you think your field will develop over the next ten years?

SC: I think that socially immunity in general will include much more network analysis and how social interaction networks affect disease-spreading. These methods have been developed only recently, and people are very interested in implementing them. You can also make a more general impact: Of course, ants are very different from other societies, but if it comes to the prevention of a disease spreading, interaction networks play a crucial role in all social groups. We can use social insects as a model system because we can observe and replicate everything and then analyze the pathogen spread, for example, by molecular markers. If we then combine this with theory and develop conceptual epidemiological models, these models can be used for other social groups as well.

MNB: Great, sounds like you have enough research ideas for the next couple of decades! Did you ever have a plan B of becoming something other than a myrmecologist? And do you call yourself a myrmecologist?

SC: Well yes, I am a myrmecologist, but I would rather call myself an evolutionary ecologist, because I see ants as a very good model to answer the questions I am interested in. I have not been an “ant person” since I was five years old, but I think these superorganismal societies are extremely fascinating. I never really had a concrete plan B, no. In my career, I was always trying to follow the questions I was most interested in, and I learned to trust my instincts, rather than choosing questions and methods strategically. I followed what I was most excited about and used whatever needed to be used to answer these questions.

MNB: That sounds wonderful! And what do you enjoy most about doing research on ants?

SC: I think I have found my way of doing science, which is small, short-term experiments. I do exclusively lab work, and I really like this controlled setup, this constant shaping and evaluation of experimental design, keeping some parameters stable and changing others – I find this type of work really satisfying!

MNB: Is there something you wish everybody knew about ants?

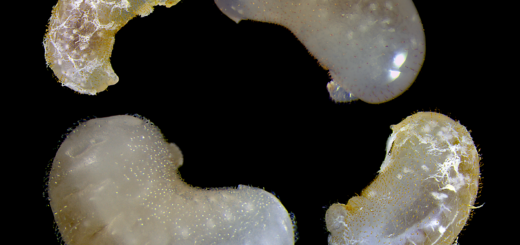

SC: When talking to non-myrmecologists, I find it astonishing that many people don’t know all worker ants are female. And the other thing is when people talk about “ant eggs” when they mean pupae – I would like them to know that. People often stumble across the fact that I am an ant researcher and have no idea what that means – so I would like to show them that ants are not just a nuisance in your garden or kitchen, but really fascinating societies actually worth a closer look!

MNB: Speaking of ants in the kitchen – how would you get rid of them?

SC: I actually tell people I don’t know, because we put a lot of effort into rearing them instead of killing them. Basically, just use a kitchen towel to remove the streets. But it’s actually not a problem to have a few visitors in the house if they don’t cause allergies or destroy the wood. Then you can start worrying.

MNB: That’s a good strategy! As you said, most ants are female, so they have the matriarchy all figured out. But how about humans? What are your views on gender equality in your field and in your working group?

SC: My working group is actually female-biased and has been for quite some time. It depends quite a bit on the discipline and behavioural ecology is one of the fields with the highest female percentage. But in all fields, we see this drop in the female percentage after the PhD, which there is a lot of awareness of. Institutes try to hire more females in higher positions, but the problem is that there are not enough candidates. So the hiring strategies are very supportive nowadays but it is a slow process. Here at the IST, the application rate for professorships is only 18% females. I am not sure what the reasons are. In my work group, we have had nine babies in the past ten years – including my own – so maybe I can act as a role model that it is possible to combine work-intense positions with family. But mothers still tend to have a harder time combining family and career and are more prone to take on a different job. In science, couples are often both scientists with flexible hours, but often do not have a job in the same city, which is extremely difficult with a small child. So it’s important to support families – this is actually done here, we have a kindergarten on campus, where kids can go from a very young age. And I always say that my husband also has two kids, not just me, and for us it has worked well because we tried to make it happen.

MNB: Great to hear that this institute is so well equipped in that regard! And what would be your main advice for someone who is just getting into myrmecology?

SC: Find out what you are most interested in and then follow up on that! Don’t necessarily follow the main trends for strategic reasons.

MNB: That’s great advice! Do you have any favorite situations to help you think about new ideas or scientific avenues?

SC: For me, it’s a mix of conferences and smaller discussions, getting exposed to other researchers, bouncing my own ideas off of them… but then I need some time to myself to digest it all, often when travelling back from a conference or sitting in nature. It’s good to step back from your daily business from time to time and ask yourself where you want to go.

MNB: Do you have a favorite phenomenon that occurs in ants?

SC: What I find fascinating is the amazing flexibility in ant colonies to introduce clonality – some species have sexually produced workers but clonal queens… this diversity of social structures is fascinating!

MNB: That really is awesome! Now just some very short questions. What’s the book on your bedside table?

SC: It’s a crime novel by Charlotte Link, “The Other Child”

MNB: Watching or doing sports?

SC: Doing sports… swimming and running

MNB: Listening to or making music?

SC: Listening

MNB: Evening or morning?

SC: Morning

MNB: Tea or coffee?

SC: Coffee

MNB: Sugar or sweetener?

SC: None

MNB: Cooking yourself or eating what someone else cooked?

SC: Both

MNB: Habit or change?

SC: Both in combination

MNB: Aspirator or forceps?

SC: Aspirator

MNB: Field or lab?

SC: Lab

MNB: Paper reprint or PDF?

SC: PDF nowadays

MNB: Journals financed by the author (open access) or the reader (subscription)?

SC: Open access, if possible

MNB: Kin selection or group selection?

SC: Colony level selection!

MNB: Monodomy or supercoloniality?

SC: Supercoloniality

MNB: Worker or queen?

SC: Our queens never do anything in social immunity… so, worker!

MNB: Your favourite ant?

SC: Cardiocondyla obscurior

MNB: Thank you so much for this very nice interview!

Recent Comments