Ant crickets associated with the invasive yellow crazy ant Anoplolepis gracilipes

Together with six colleagues, Brian Po-Wei Hsu recently published a part of his Master’s thesis in the Myrmecological News article “Ant crickets (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae) associated with the invasive yellow crazy ant Anoplolepis gracilipes (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): evidence for cryptic species and potential co-introduction with hosts”. In this interview, we talk about the paper, his research, and the fascinating lives of ant crickets.

Interview compiled by Alice Laciny

MNB: Could you tell us a bit about yourself and what you do?

PWH: My name is Brian, and I just graduated from the Lab of Urban Pestology in Kyoto University. So I only got my Master’s degree last year. I am currently working in Taiwan as a research assistant in the Lab of Social Insects at National Changhua University of Education. I’ve been working with ants for about 12 years since I was a little kid (at that time it was for some small projects for the science fair). Luckily, I was able to choose entomology as my major when I entered college and keep doing my ant studies. In my Master’s I changed my topic to ant crickets, and now I’m back working on ants and preparing to apply for a PhD course this year.

MNB: Very nice, good luck with the application! Was your new paper in Myrmecological News part of your Master’s thesis?

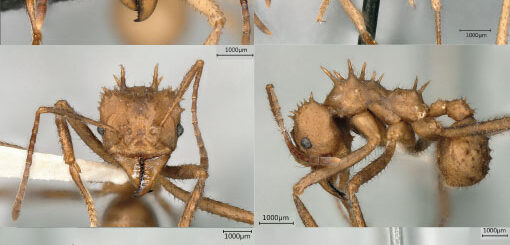

PHW: Yes, it’s the first part of my thesis. It’s a taxonomic revision of the ant crickets found with yellow crazy ants, using both morphological and molecular information. The second part is about the phylogenetics of worldwide ant cricket species, which cover all existent 3 genera and roughly 1/4 of the total described ant cricket species.

MNB: Could you summarize your paper on ant crickets associated with Anoplolepis gracilipes you published in Myrmecol. News in simple terms?

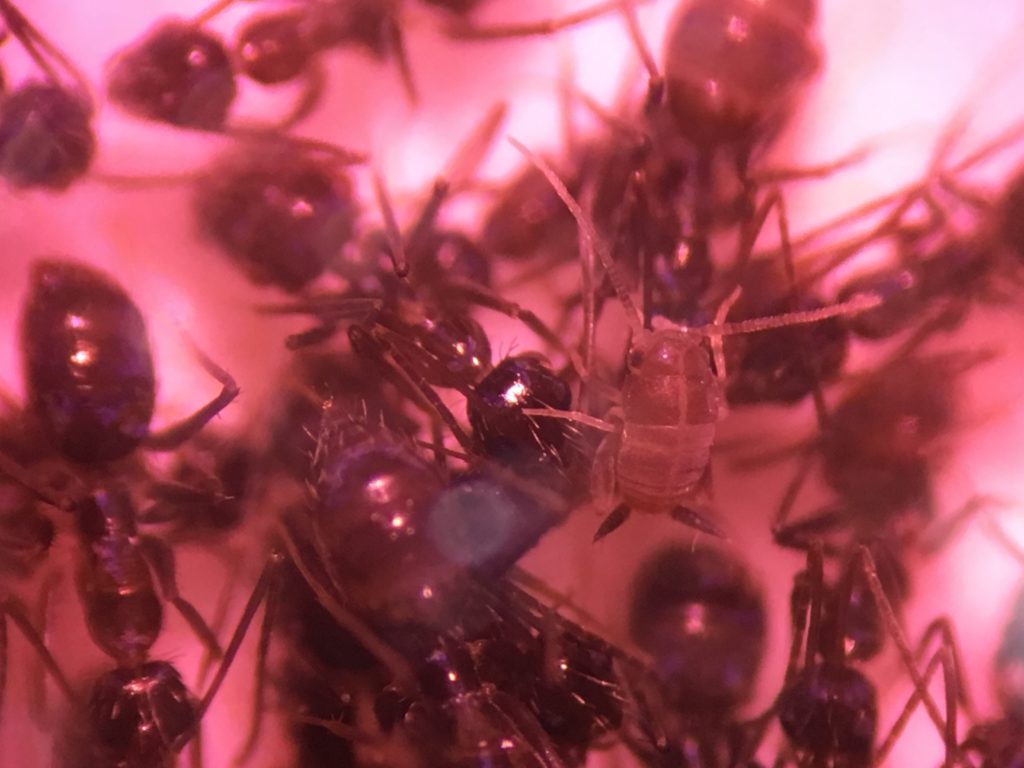

PWH: Ant crickets are very cute insects living with ants. In this paper, I combined morphological and molecular data to identify ant crickets found with a well-known invasive species, the yellow crazy ant. This ant is mainly distributed in Indo-Pacific regions, and the associated crickets were actually being carried together with their hosts. We proposed new taxonomic treatments for these crickets and found that some species are now widely distributed in the Indo-Pacific regions as well.

MNB: That’s very interesting! So what is the main take-home message of your work, the most important finding?

PWH: We showed that molecular data is helpful to identify these crickets across Indo-Pacific regions, and provided a new idea of how human-mediated transportation may influence our ecosystem: Not only invasive ants can destroy local ant/arthropod communities, but the associated ant crickets can also be carried together and potentially threaten native cricket species. Local ant cricket communities might be affected in both ways.

MNB: What was your motivation to conduct this study?

PWH: It is actually a long story. Research topics of our lab in Kyoto mainly focus on the invasive ant species, and one of my seniors was working on longhorn crazy ants. Part of her research is about Wolbachia, and after we found ant crickets in the nests, she thought that maybe Wolbachia can be horizontally transferred between ants and crickets. That’s why we started working on crickets. It was quite difficult at the beginning because almost no one was working on ant cricket taxonomy, especially for those living with invasive ants. By that time, I was about to start my Master’s course, so I decided to work on ant crickets, and the first question that came up was of course about their taxonomy. So we went from longhorn crazy ants to Wolbachia, then to the ant crickets living associated with longhorn crazy ants, finally to other ant cricket species, including the ones in yellow crazy ants.

MNB: Oh wow, what a journey! It’s great to have someone who knows ant crickets now. What was the biggest obstacle you had to overcome in this project? Was it hard to get enough material?

PWH: For ant cricket studies, I would say the hardest part is indeed to get samples, so I always appreciate the chance to get material from others. Those samples were almost all given to me by other scientists because the crickets are usually inside the nest and hard to be collected. Luckily the cricket species in this study are mostly associated with the invasive ants, so getting enough crickets is relatively easy. And thanks to our collaborators, I was able to get crucial samples from some distant islands. The other difficult part for me is about getting those old taxonomic papers. Some of the papers you can find on the internet, but for the others, I had to access several libraries in order to get all of the publications for my target regions. The crickets in this study are widely distributed in the Indo-Pacific region, so finding a paper of a Bornean or Indian species was quite challenging to me.

MNB: Do you have any tips for others who are interested in doing related research?

PWH: I think the most important one is, if you want to collect crickets – especially from a yellow crazy ant nest – you better get a hand-vacuum which you can carry into the field. Because when you open up their nest, crickets can disappear within seconds, and it is very hard to get them among those panicking workers and formic acid smells. So you have to get the collecting tool right. And if you want to work on their behavior, you have to keep your crickets separated from the ants! Once you put them in a confined container, most of the crickets will be killed since the nervous ants will quickly realize who is not their nestmate. Even extremely specialized crickets are fragile and sometimes get killed in our artificial nests. So raising crickets separately or at least reducing the number of host workers is necessary to keep them alive.

MNB: Where do you see the future for this particular field of ant research within the next few years?

PWH: I think their taxonomy and phylogenetics still have a lot to be done, especially for those crickets associated with native ant species. Chemical mimicry will be a very important topic as well. I heard that people from Dr. Tsutsui’s lab at UC Berkeley are working on related topics. Different ant crickets were reported to have different kinds of behaviors and strategies: Some of them get the chemicals from the ants by licking the ant’s body and putting those on their own body, while other species don’t show this behavior but can still live with the ants. This would be a very interesting field!

MNB: That’s really fascinating! Last question: We really like to focus on diversity when interviewing for MNB. In a future interview, whom (researcher, PostDoc fellow, or PhD student) would you like to see featured? Please name three persons with at least 50% females included?

PWH: The first one who comes to my mind is Dr. Corrie Moreau, because her lab would be one of my ideal labs for doing my PhD. The other one is Dr. Nathalie Stroeymeyt from University of Bristol, she is working on ant epidemiology. In her recent Science paper, she used QR codes to track ants’ movements, which is quite fascinating. The last one is Dr. David Hughes, who wrote lots of papers on zombie-ant fungi. They are also a kind of myrmecophilous parasites, so I find them really interesting as well.

Awesome work and interesting interview!