First record of the genus Overbeckia in Australia

In the recently published article “First record of the formicine genus Overbeckia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Australia” in Myrmecol. News, author Brian Heterick describes specimens of the rarely found genus Overbeckia and discusses the implications of this finding. Here, Gabriela Pérez-Lachaud highlights his main points that entomological collections often harbour a great hidden diversity that should not be underestimated.

A View by Gabriela Pérez-Lachaud

How many species exist on earth? How many species are left to discover? These are two recurrent questions in Biology, and despite centuries of work by taxonomists all over the world, and decades of exploring both some of the most familiar and remote places on Earth, biodiversity scientists estimate that more than 80% of species remain unknown to the present day (e.g., Stork 2018). Most researchers agree that those species left to discover are very small (mostly microorganisms), live in habitats with low accessibility, have cryptic life histories or represent cryptic species in species complexes that can only be discriminated through integrative taxonomy and multidisciplinary studies. Researchers also agree that many new taxa with elusive life histories remain undiscovered, even in the best-studied parts of the world, not to mention in biodiversity hotspots in developing countries.

However, many new species are likely already in collections all over the world, as the recently published article “First record of the formicine genus Overbeckia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Australia)“, by Brian E. Heterick (Myrmecological News) demonstrates. In this study, Brian Heterick reports the finding of a species (possibly a new species) of these cryptic ants among ants collected in 2002 in the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia by amateur Raul Jordan, and donated to the Western Australian Museum in 2018. Overbeckia specimens were collected along with a colony of Colobopsis nesting in a dead hollow twig. Revision of the material revealed the presence of peculiar specimens that were later identified as belonging to a different genus.

The genus Overbeckia currently contains a single species, Overbeckia subclavata Viehmeyer, 1916 and had not been recorded in Australia previously; in fact, for many years this group of ants was known only from the types. Almost nothing is known about the nesting habits of Overbeckia ants, and the little biological information available suggests workers are nocturnal and arboreal. These habits at least partially explain their infrequent collection. Interestingly, the sample of Overbeckia was obtained not from the heart of a remote rainforest, but within disturbed remnant vegetation on the periphery of a large town. This finding thus represents the first record of Overbeckia ants for Australia, but whether these ants are native to Australia and had been overlooked in the past or whether they have recently been introduced into Australia is uncertain. Further, the Raul Jordan Collection is not only important for the number of native ant species it contains but also because it represents the first records in this country of two other unquestionably exotic species; namely Cardiocondyla minutior Forel, 1899 and Solenopsis papuana Emery, 1900. The work by Brian Heterick both highlights the value of amateur collections and reinforces the notion that material already stored in collections is an important source of new species for science.

Each year, new species are added to Earth’s tree of life. Usually, new species are identified on the basis of new collection efforts and through discriminating among cryptic species, but new species are also described by studying material stored in natural history museum collections, which hold a large quantity of unsorted, unidentified, or misidentified material. Natural history collections around the world are thus expected to contain a significant amount of new, still undescribed taxa. For example, early in December 2019, researchers at the California Academy of Sciences announced 71 new species of plants and animals (including three ants), discovered that year across five continents in cryptic (or very difficult to access) habitats and at extreme ocean depths. Notably, Myrmecicultor chihuahuensis, the first – and only – species in a new family of “ant-worshipping” spiders (Araneae: Myrmecicultoridae) was found in ant nests, and a rare white-blossomed plant, Trembleya altoparaisensis (Melastomataceae), was described based on several specimens collected over 100 years ago (Pacifico et al. 2019)! The discovery of trophic interactions in material stored in collections is possible. Ant-parasitoid interactions, for example, have been discovered revising material stored in collections, on at least two occasions (e.g., Pérez-Lachaud et al. 2012, Pérez-Lachaud and Lachaud 2017), including the first record of a tiny encyrtid wasp parasitizing ant pupae which was found after 10 years storage in alcohol. These studies and the results reported by Heterick suggest that examining insect material already housed in collections will certainly result in the discovery of species new to science.

We have a long way to go until a catalog of those species already in collections is completed, and this issue is exacerbated by the worldwide lack of taxonomists, which has a broad impact on biology and society. There is much of a debate on this issue but see https://www.cbd.int/gti/problem.shtml. Identified species of arthropods make one of the largest contributions to overall global species richness, and many more species are expected to be discovered at diversity hotspots, however many of these unidentified species may become extinct before we discover them.

Brian E. Heterick, author of the paper

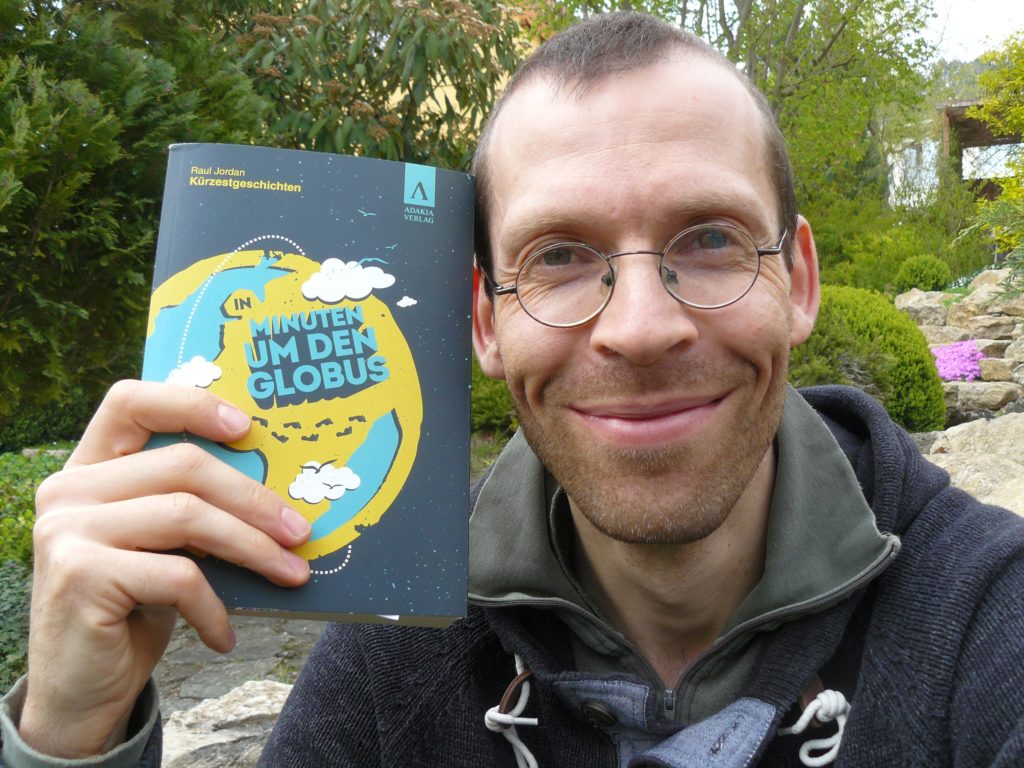

Raúl Jordan, the visiting amateur who collected Overbeckia

References

Pacifico, R., Almeda, F., Do Carmo, A.A. & Fidanza, K. 2019. A new species of Trembleya (Melastomataceae: Microlicieae) with notes on leaf anatomy and generic circumscription. – Phytotaxa 391: 289-300.

Pérez-Lachaud, G., Noyes, J. & Lachaud, J-P. 2012. First record of an encyrtid wasp (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) as a true primary parasitoid of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). – The Florida Entomologist 95: 1066- 1076.

Pérez-Lachaud, G. & Lachaud, J-P. 2017. Hidden biodiversity in entomological collections: The overlooked co-occurrence of dipteran and hymenopteran ant parasitoids in stored biological material. – PLoS ONE 12: e01846

Stork, N.E. 2018. How many species of insects and other terrestrial arthropods are there on Earth? – Annual Review of Entomology 63: 31-45.

Recent Comments