Jobs – how to?

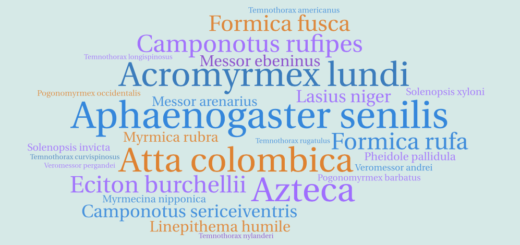

Decisions about positions can be crossroads – Making the right choice can be key to success and happiness. And obviously, this applies to both sides, the applicant’s and the employer’s. We think that bringing to light some of the bases for decision-making used on the two sides could be interesting to both. Find here how seven more junior and nine more senior ant researchers from 12 nations approach the topic of PhD-student and Postdoc positions.

Flash interviews compiled by Florian M. Steiner

Nathan J. Sanders, United States of America, on recruiting PhD students and Postdocs

MNB: When screening written applications, what are the sections you are most eager to read?

NJS: Prior research and future research plans.

MNB: What are your personal deal-breakers in application letters and CVs?

NJS: If it’s clear the applicant hasn’t done their homework, either about the work our lab has done or the classic papers in the field, it’s a deal breaker.

MNB: At the interview stage, do you ask the applicants to do any hands-on tests?

NJS: Sort of. One is top secret, so I won’t reveal it. The other is that I have sometimes sent a dataset to the final four or five applicants and told them to do something interesting with it.

MNB: In deciding for the successful applicant, what weighs more for you – education and the publication record or the applicant’s personality as you experienced it?

NJS: Honestly, both are equally important. Someone could have several papers published in important journals and be the next great myrmecologist since Andy Suarez. But if they’re a jerk and won’t fit in with the group, I don’t want to accept them.

MNB: Do you find the decision-making process in personnel recruitment easy or difficult?

NJS: It’s been easy to decide who the final two or three candidates for a position are. Then it gets challenging. It’s also hard to say no to people who know are going to go on to do great things, but either you don’t have the funding, or it’s just not quite the best fit.

MNB: What is your most important advice to young scientists seeking a position?

NJS: Do what’s interesting to you, make sure you like your mentor (and that they will mentor you), and figure out how to have good balance between your work and non-work lives.

Christina L. Kwapich, United States of America, on applying for positions

MNB: When screening announcements of positions, do new challenges rather intimidate or attract you?

CLK: An important part of my PhD and postdoctoral training has been to expand my toolkit. I am attracted to positions that allow me to pick up new methods, while still asking the questions I think are important. You can learn anything if you take it step by step and find the right people to pester!

MNB: In deciding for which positions to apply, what is important for you (the topic, the working group, the geographic location, the salary, etc.)?

CLK: Sharing a compatible personality and philosophy of science with one’s advisor is the most important aspect of choosing a position. For me, the second most important aspect is geographic location. I like to get out to the field in all seasons and enjoy having interesting ants at my fingertips. So far, I’ve been lucky enough to work with the generous mentors in locations with many fine ants (Florida and Arizona, USA).

MNB: At the interview stage, are there questions you would rather not be asked, even though they are politically correct, and if so, why?

CLK: I would welcome any professional questions.

MNB: In considering whether to accept a position you are offered, what weighs more for you – the scientific standing of the employer or the employer’s personality as you experienced it?

CLK: For me, an employer’s personality is much more important than the prestige of an institution. If “scientific standing” is meant to describe an employer’s expertise and research practices, then I would say those should be considered very carefully. As a graduate student, your mentor’s behavior is a template for how to approach your first research question, first academic conflict, your work/life balance, feelings about funding and more. It is important to have the right template.

MNB: Do you see a PhD or Postdoc position as part of your education or rather as a paid job?

CLK: I view my postdoc as part of my education and also as my first real job. I continue to learn from wiser people and to develop new skills – but I can do the things I practiced as a graduate student at an accelerated pace. It has been fun to form collaborations with postdoctoral colleagues at this stage, because I see what I bring to the table as a researcher, independent of my mentors.

MNB: What is your most important wish for potential employers in deciding for the successful applicant?

CLK: A good scientist needs to be creative. GRE scores and GPAs don’t measure originality or resourcefulness. So, I would look for other clues when selecting a PhD student. Postdocs are scarce. When assessing an applicant, consider whether his or her brand of science should continue in our field. If you don’t give the applicant an opportunity, they may not have another chance.

Elva J.H. Robinson, United Kingdom, on recruiting PhD students and Postdocs

MNB: When screening written applications, what are the sections you are most eager to read?

EJHR: Personal statement – because I am interested it what motivates the candidate and what specifically interests them about the project.

MNB: What are your personal deal-breakers in application letters and CVs?

EJHR: For positive deal-breakers, there isn’t one thing – there are many different ways an application can stand out positively. A real deal-breaker in the negative sense is a generic application that doesn’t demonstrate any specific interest in the project. A PhD student needs passion for the subject to carry them through the bad times.

MNB: At the interview stage, do you ask the applicants to do any hands-on tests?

EJHR: Not so far, but I might now consider this …

MNB: In deciding for the successful applicant, what weighs more for you – education and the publication record or the applicant’s personality as you experienced it?

EJHR: I try very hard not to be swayed by interview personality, as some people interview easily, and others find it more challenging to be relaxed and open when they are being assessed – but this says more about background, interview experience and confidence than about research ability. I try to listen to the content of responses rather than being distracted by the presentation – though of course good communication skills are a plus.

MNB: Do you find the decision-making process in personnel recruitment easy or difficult?

EJHR: I find it very challenging, because often multiple applicants shine in different ways, so are very difficult to compare. I also greatly dislike having to turn down people who are clearly enthusiastic and capable!

MNB: What is your most important advice to young scientists seeking a position?

EJHR: Don’t be disheartened by initial rejections, just add them to your application/interview experience set, and keep going. And only apply to projects you really want to do – as above, you need to care about the content of the project enough to keep you going through any bumps in the road along the way.

Krzysztof Miler, Poland, on applying for positions

MNB: When screening announcements of positions, do new challenges rather intimidate or attract you?

KM: Pre-requirements for positions usually “sieve off” all options which would be (too) intimidating for me and leave only those which are within my reach. So what I’m left with are attractive options, each with “new challenges”, which are always there when you change a position.

MNB: In deciding for which positions to apply, what is important for you (the topic, the working group, the geographic location, the salary, etc.)?

KM: I guess it really depends on how well does the position fit into my “agenda” of improving my overall standing. A well-paid and long-term abroad postdoc with potential for fruitful collaboration would be ideal at this point of my career, but there are other options I would consider. For example, I would probably go for an internship or a short-term research stay somewhere, despite some cons, if only it would allow me to significantly advance myself as an expert. That’s, because I’m young and motivated and crazy about finding things out.

MNB: At the interview stage, are there questions you would rather not be asked, even though they are politically correct, and if so, why?

KM: Maybe questions not strictly related to the job, like “what do you do outside of work?”, which are still sometimes asked… But that’s because if I would answer honestly, then I would end up with a “weirdo” label. Not so good for getting hired.

MNB: In considering whether to accept a position you are offered, what weighs more for you – the scientific standing of the employer or the employer’s personality as you experienced it?

KM: The latter! People can really stay in your way at every stage of your career, and if the employer is not a good match for you, then many things can go really wrong, no matter “the standing”. I experienced it, and I have numerous colleagues with the same experience. It’s best, of course, if you can choose between employers which are more or less comparable in their standing but differ strongly in how you experience them. Rare occasions.

MNB: Do you see a PhD or Postdoc position as part of your education or rather as a paid job?

KM: It’s a job, and I don’t think that it’s a matter of opinion. Of course, you still educate yourself, but there is a clear difference between getting a degree and education after assuming a position. Acts and responsibilities that make up this difference sum up into a difficult job.

MNB: What is your most important wish for potential employers in deciding for the successful applicant?

KM: To realize that different backgrounds and stories are not a bad thing. Science is a team effort, and a bit of diversity in a team is good for everyone.

Laurent Keller, Switzerland, on recruiting PhD students and Postdocs

MNB: When screening written applications, what are the sections you are most eager to read?

LK: It depends whether it is for a PhD student or Postdoc. For PhD students, I look at the grades in math, physics, and statistics and why they are interested in doing a PhD in my group (I only very rarely advertise positions and prefer when people apply spontaneously. For Postdocs, I look mostly at their publications and the project they want to do (I expect Postdocs to propose a project that I can discuss with them).

MNB: What are your personal deal-breakers in application letters and CVs?

LK: No simple answer …. it is a combination of aspects, in particular those mentioned above.

MNB: At the interview stage, do you ask the applicants to do any hands-on tests?

LK: No, but I ask them to give a talk in front of the whole group. We ask a lot of questions during the talk, and the applicant has to discuss with most of the members of the group. I then compile all opinion to make my own decision.

MNB: In deciding for the successful applicant, what weighs more for you – education and the publication record or the applicant’s personality as you experienced it?

LK: Both are very important. Most of my students ultimately get a permanent academic position, and I believe this is because we are very careful in choosing them well (both in terms of aptitudes and ability to interact with group members).

MNB: Do you find the decision-making process in personnel recruitment easy or difficult?

LK: I think one of my main skills is to have good judgement in selecting people, and this is the reason why I never had a graduate student stopping during the PhD and why most of my students get permanent academic positions.

MNB: What is your most important advice to young scientists seeking a position?

LK: Visit the lab and talk a lot with the students to investigate whether you will have the right environment for you. Some students need a small group with a lot of attention from the supervisor, while others want a lot of freedom. Check that the PI and group will provide what you are looking for. If you have hesitation, do not take the position!

Enikő Csata, France, on applying for positions

MNB: When screening announcements of positions, do new challenges rather intimidate or attract you?

EC: To be honest, I would say both. For example, when I was applying for my current position, I had no experience working with nutrition on ants, only ants and their parasitic fungi. Whilst I found this quite intimidating, I also saw it as a chance to overcome my fears and strengthen myself as a researcher. By challenging my fears of failing, I have learnt many new techniques and approaches that I can bring with me into my future research. Ultimately, this has increased my confidence as a researcher and given me a strong sense of personal achievement.

MNB: In deciding for which positions to apply, what is important for you (the topic, the working group, the geographic location, the salary, etc.)?

EC: To me, the most important thing when I select a position is the working group, its environment and the topic. From previous experience, I know how important the working environment is for supporting members of the group when facing new challenges and periods of pressure. It is important for me to work in a group where everyone is very open and willing to talk about the problems they may be having with their work and how to solve them. This is what I love most about my current research group (IVEP, Université Paul Sabatier); there is an open and friendly atmosphere where we constantly discuss our research. This not only provides solutions to our problems but also motivates us to work to the best of our ability. I also believe this is strengthened by the social side of the research group. As well as socializing at work, we also meet up outside of working hours to hang out. This has helped me settle quickly in Toulouse from both a work and personal perspective. After the work environment, the most important thing to me is the research topic. If you are not truly interested or excited in a topic, it is better that you don’t go for it. We often face difficult problems working in research, so if the core interest is not there, it will be impossible to get through the tough times.

MNB: At the interview stage, are there questions you would rather not be asked, even though they are politically correct, and if so, why?

EC: So far, I have not been asked a question in an interview that would make me feel this way. However, I can imagine feeling uncomfortable if I were asked a question that would involve me judging the success of my previous work. This is not because I have a negative view of my work, it is just that I feel uncomfortable making that judgment myself.

MNB: In considering whether to accept a position you are offered, what weighs more for you – the scientific standing of the employer or the employer’s personality as you experienced it?

EC: For me the employer’s personality weighs much more than the scientific standing. You cannot work well with a person if you do not connect with them on a personal level, no matter what their scientific standing is. I believe that the best and most enjoyable science comes from a collaborative process, sharing ideas and solving problems together. If you don’t feel comfortable approaching your supervisor with a problem or a new idea, then your potential is being wasted.

MNB: Do you see a PhD or Postdoc position as part of your education or rather as a paid job?

EC: My PhD definitely felt like part of my education. In contrast, my current Postdoc position (since January 2018) feels more like a proper job. I don’t feel like a student anymore, I’m more independent, I’m more confident, I have to make decisions on my own, and I have to take responsibility both for my work and for the students I’m supervising.

MNB: What is your most important wish for potential employers in deciding for the successful applicant?

EC: Nowadays, there seems to be a lot of focus on the CV, the list of publications and the grants gained by the applicant. Whilst this is understandable in a career as competitive as academia, I would hope that potential employers would equally consider the motivation and personality of the applicant. The number of publications you have or the size of the grants you’ve won do not necessarily reflect your worth as a researcher. I would suggest that employers ask not just a list of publication but also a motivation letter where they can get a feeling for the applicant’s personality. I think the goal of the employer should be: to find someone who is enthusiastic and motivated about the research that they will do.

Neelkamal Rastogi, India, on recruiting PhD students and Postdocs

MNB: When screening written applications, what are the sections you are most eager to read?

NR: The details of both the academic and non academic achievements are important to assess the overall learning trajectory and caliber of an applicant, so I go through both these sections.

MNB: What are your personal deal-breakers in application letters and CVs?

NR: I am interested in the information which can give me a picture about the candidate’s areas of interest(s), degree of motivation and passion towards the relevant scientific field. Since I work in the field of Zoology (area of interest being Behavioural Ecology), I am interested in deciphering the candidate’s scientific potential and interest in the relevant area. What exactly has the candidate done during his/her free time? The spirit of enquiry and curiosity is often reflected by the academic as well the non academic interests and hobbies, for instance, an interest in nature! A person with an intrinsically scientific bent of mind is curious about what is happening in the surrounding environment, has interest in understanding how it is happening. Extra-curricular pursuits and hobbies (such as bird-watching, observing insects, reading, gardening etc.) also help in gauging the candidate’s actual interest and extent of commitment. Does the candidate possess an ability to formulate ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions? Even simple projects carried out by the student can be informative in terms of the aspect(s) examined, questions asked, quality and commitment towards the work carried out.

MNB: At the interview stage, do you ask the applicants to do any hands-on tests?

NR: No.

MNB: In deciding for the successful applicant, what weighs more for you – education and the publication record or the applicant’s personality as you experienced it?

NR: In my opinion an interviewer cannot disregard the academic facts and focus only on the latter and vice versa. While the education and publication record provides information about the knowledge base in science and the individual’s academic ability, the personality traits are indicative of the degree of clarity and motivation of the candidate.

MNB: Do you find the decision-making process in personnel recruitment easy or difficult?

NR: It is interesting, challenging and not too difficult.

MNB: What is your most important advice to young scientists seeking a position?

NR: i. First and foremost, once you are sure that you love doing science, put your heart and soul in your work and go ahead!

ii. Apart from doing active research in the area of your interest, it is important to reflect how you can analyze and interpret your data and explore new dimensions. You need to be receptive to new ideas (for instance, field observations often provide novel ideas). A habit of regularly reading recent research publications in diverse subject areas also leads to germination of new ideas. Interactions with other scientists (including those working in other disciplines such as physics, chemistry, engineering etc.), can prove to be very helpful in looking at your findings from different perspectives.

iii. Problems are likely to arise at various points of time. Do not let these deter you. Be patient, persistent and passionate about your work and eventually you will be able to do something meaningful and satisfying in your research career.

Moataz Noureddine, United States of America, on applying for positions

MNB: When screening announcements of positions, do new challenges rather intimidate or attract you?

MN: I care more about whether the challenges are fair or not. I am always excited about growing as a young scientist. I only feel discouraged when it’s out of my control like funding, for example.

MNB: In deciding for which positions to apply, what is important for you (the topic, the working group, the geographic location, the salary, etc.)?

MN: I believe that so much goes into choosing which positions to apply to. Some things I would not compromise on would be topic and working group. I believe that I need to choose a topic that I am passionate about to go in depth in. I also think that it’s important to have a motivating environment. On the other hand, even though I do keep them in mind, I can compromise on geographic location and salary. I think that the PhD experience compensates for the location. From what I have experienced, PhD students can spend more time in lab than outside of it. I also believe that the degree will compensate for the low PhD stipend after graduation.

MNB: At the interview stage, are there questions you would rather not be asked, even though they are politically correct, and if so, why?

MN: I believe that I would learn a lot about the institute from the questions they ask so I would like to know more about what they focus on when it comes to candidates. Some questions that are irrelevant to the field and the program could make me uncomfortable but are still necessary for me to create a better image of the institute.

MNB: In considering whether to accept a position you are offered, what weighs more for you – the scientific standing of the employer or the employer’s personality as you experienced it?

MN: I believe that I would only let their personality intervene in my decision if I felt like they will lay more obstacles in my graduate path than opportunities. Other than that, I will care more about their scientific standing because that will give me better insights about the research funding they can acquire and the connections they can provide for collaborations.

MNB: Do you see a PhD or Postdoc position as part of your education or rather as a paid job?

MN: I believe it’s an educational experience. Even though PhD students could be doing a lot of the lab work as research assistants, I believe that they are learning other skills that some working positions are not. Other than the classes they need to take, I believe that in the lab they learn how to connect all the different experiments and projects in a paper format, which not all lab positions are required to do. I also believe that many programs have paper review meetings that happen often and many other events and activities to stimulate growth in their PhD students.

MNB: What is your most important wish for potential employers in deciding for the successful applicant?

MN: I wish they look at more than grades and scores. I hope they look for a well rounded application and understand that standardized tests are not always fair. When it comes to unsuccessful applicants, I hope that they keep transparency with their applicants and inform them once they finished inviting students for interviews and not keep them hanging for months before they give them any update.

Philip J. Lester, New Zealand, on recruiting PhD students and Postdocs

MNB: When screening written applications, what are the sections you are most eager to read?

PJL: For any application to the university, I think most people typically go straight to the publication record. Where you got your PhD, who you did your graduate work with, or what roles you’ve had, are all of much less of a priority for me. Post-doctoral funding typically comes from grant proposals, and the funders want to see a successful programme with research that will be published in good outlets. Your previous publication track is the best predictor of your future productivity.

MNB: What are your personal deal-breakers in application letters and CVs?

PJL: Deal-breakers can come in all sorts of ways. Though they typically aren’t in application letters and CVs, they often come from the reference letters. I suggest you pick your referees carefully.

MNB: At the interview stage, do you ask the applicants to do any hands-on tests?

PJL: I don’t ask candidates for hands-on tests. But such tests are being increasingly used for science positions in government roles here in New Zealand.

MNB: In deciding for the successful applicant, what weighs more for you – education and the publication record or the applicant’s personality as you experienced it?

PJL: The publication record is of primary importance. But I also want the candidate to enjoy working with our team, and for my research group to enjoy working with the candidate. So, personality and fit are really important. The applicant’s personality is one of the first things I’ll discuss with referees.

MNB: Do you find the decision-making process in personnel recruitment easy or difficult?

PJL: That depends on how many applicants and quality candidates there are for a role. It isn’t easy when there is a pool of people who would all be great. Typically, there is funding for just one person. I don’t enjoy turning down people whom I’d like to employ.

MNB: What is your most important advice to young scientists seeking a position?

PJL: I’d encourage both post-doctoral applicants and students seeking to do

Swati Pant, United States of America, on applying for positions

MNB: When screening announcements of positions, do new challenges rather intimidate or attract you?

SP: It is a bit of both. It’s exciting because I get to know about all the interesting projects people are working on, which I could potentially become a part of. It’s also nerve wracking, as my submission of an application doesn’t guarantee acceptance and I have to deal with my fear of rejection and my general discomfort with it as well. There are also times in which I feel like I shouldn’t apply for a posted position, despite fulfilling the requirements and having the appropriate qualification, simply because I feel like I won’t be accepted. I also try to research the work environment and the supervisor or principal investigator I may be potentially working under during my application process but feel rather apprehensive about it, as a healthy work environment and quality mentorship are factors that affect job satisfaction.

MNB: In deciding for which positions to apply, what is important for you (the topic, the working group, the geographic location, the salary, etc.)?

SP: The most important aspect for me is the working group. As a PhD student, you are still learning and looking for a specific topic of interest. A great working group allows you to engage meaningfully with the research project and increases your confidence as a scientist. While in a bad working group you may start to rethink your choices and lose confidence in yourself and your topic, even if you are working on a project within your field of interest. I think that the working group impacts the kind of scientist you are, how you approach problems as well as the way in which you approach a scientific question.

MNB: At the interview stage, are there questions you would rather not be asked, even though they are politically correct, and if so, why?

SP: “What do you want to do after your PhD?” – I feel that this question sets candidates to feel that choosing a path that is outside academia is frowned upon. Getting a PhD can take from 4 to 6 years, and asking that question seems premature, as a PhD program is supposed to be a learning opportunity where you get exposed to different areas and aspects of science, which will help you make an informed decision on your path after the PhD. I think a better question would be, “What do you hope to learn and achieve from your PhD?”.

MNB: In considering whether to accept a position you are offered, what weighs more for you – the scientific standing of the employer or the employer’s personality as you experienced it?

SP: The employer’s personality matters more to me as it has to be compatible with mine. Conflict with your employer never leads to any good. Their personality also determines the kind of work environment and relationship you have with them. PhD programs are already a lot of work and stress, and having an employer who supports you makes things a little easier.

MNB: Do you see a PhD or Postdoc position as part of your education or rather as a paid job?

SP: I see a PhD program as a part of my education, as it would help me increase my knowledge in a specific area of study while also helping me develop myself as a researcher. The program also gives me an opportunity to work with a mentor who is essential in providing me guidance throughout my PhD. I would also be learning different techniques that are transferable to different projects.

MNB: What is your most important wish for potential employers in deciding for the successful applicant?

SP: I hope that potential employers look at an applicant’s interest in the field of research as well as at their attitude towards work. I hope that they also try to recruit employees from different backgrounds so as to have more diverse perspectives and more wholesome discussions.

Zhanna Reznikova, Russian Federation, on recruiting PhD students and Postdocs

MNB: When screening written applications, what are the sections you are most eager to read?

ZR: Research interest and background.

MNB: What are your personal deal-breakers in application letters and CVs?

ZR: Ordinary words; non-concrete, streamlined expressions.

MNB: At the interview stage, do you ask the applicants to do any hands-on tests?

ZR: Yes, I ask the applicant to colour-mark the ants and to show that he/she can handle them.

MNB: In deciding for the successful applicant, what weighs more for you – education and the publication record or the applicant’s personality as you experienced it?

ZR: Education and the publication record are important; however, the applicant’s personality weighs more for me. It is crucial for me to understand whether the applicant will be careful enough, responsible and patient in experimental work, whether he/she will not be disappointed when getting a negative result time after time, will show sufficient creativity if he/she has to change the methodology.

MNB: Do you find the decision-making process in personnel recruitment easy or difficult?

ZR: Rather difficult.

MNB: What is your most important advice to young scientists seeking a position?

ZR: You should be enthusiastic and love ants.

Alexandre C. Ferreira, Brazil, on applying for positions

MNB: When screening announcements of positions, do new challenges rather intimidate or attract you?

ACF: In the academic career, new challenges always attract me. I think that in a research life, following new questions and solving problems make the unknown fascinating. Being open to new challenges enables us to have incredible experiences, both in professional and personal growth.

MNB: In deciding for which positions to apply, what is important for you (the topic, the working group, the geographic location, the salary, etc.)?

ACF: I think the main point that leads me to a final decision is the working group. Being in an environment with the conditions to develop good research as well as having colleagues that stimulate the team to improve is fundamental for such training stage. Successful work collaborations begin under these circumstances and help us gain experience both with work routine and with interpersonal relationships. These skills can be decisive to get a new job/position.

MNB: At the interview stage, are there questions you would rather not be asked, even though they are politically correct, and if so, why?

ACF: For me, it is not necessarily questions of personal scope that escape the context of the position for which I’m applying, even if they are politically correct. I believe that certain subjects and topics that don’t interfere with the work routine are irrelevant in this type of interview.

MNB: In considering whether to accept a position you are offered, what weighs more for you – the scientific standing of the employer or the employer’s personality as you experienced it?

ACF: The personality of the employer, for me, is crucial, more important than the scientific position per se. Many times, employers with good positions do not care about a healthy routine in their laboratories and can often be abusive to researchers and other employees. A healthy routine with good practices and relationships is fundamental for professional development. I believe that looking for an employer who has a personality compatible with your ideals is the main point. We can earn a lot by working with an employer in a good scientific position, but if it costs our emotional health, then it is not worth it. Many people give up their own career because are living under unnecessary pressure. If you put some effort into it, you can find employers with a fitting personality, who also hold a good scientific position.

MNB: Do you see a Ph.D. or Postdoc position as part of your education or rather as a paid job?

ACF: I think they are two different situations. Ph.D. is the last stage of our scientific training, when we start to focus on one specific field and become more proficient in that. Several doctoral students also have to do teaching activities in order to pay their tuition. In this sense, this stage ends up being both part of your education and also a paid job. On the other hand, as a Postdoc, you have completed your formal scientific training, although you’ll always need to study and renew your knowledge. This is the moment in which we look to improve our curriculum with publications and professional experiences; in this sense, it is more related to a paid job than to formal education.

MNB: What is your most important wish for potential employers in deciding for the successful applicant?

ACF: For me, the most important thing is for employers to choose candidates who can contribute to the growth of the working group as a whole. A person who adds to general aspects of the workplace both in an organizational and logistical sense. In addition, helping other members, sharing knowledge and making the group more cohesive is also a desirable competence for an applicant. I wish potential employers would care about holistic contributions more than the number of publications in the candidate’s curriculum.

Anonymous Male, Germany, on recruiting PhD students and Postdocs

MNB: When screening written applications, what are the sections you are most eager to read?

AM: CV, letter of motivation, publication list.

MNB: What are your personal deal-breakers in application letters and CVs?

AM: Soundness, match with own research questions, quality of education and publications

MNB: At the interview stage, do you ask the applicants to do any hands-on tests?

AM: No.

MNB: In deciding for the successful applicant, what weighs more for you – education and the publication record or the applicant’s personality as you experienced it?

AM: Both is equally important.

MNB: Do you find the decision-making process in personnel recruitment easy or difficult?

AM: It depends on the position – sometimes, it is difficult to find the right match.

MNB: What is your most important advice to young scientists seeking a position?

AM: Do what interests you most – there you will be best.

Heike Feldhaar, Germany, on recruiting PhD students and Postdocs

MNB: When screening written applications, what are the sections you are most eager to read?

HF: In applications for PhD positions it is very important to me that it becomes evident that the applicant has a genuine interest in the field of research. Why is this person applying? A general statement “…have always been interested in your field of research…” is not enough here. Students just finishing their master thesis cannot be expected to have published anything yet. This would be very important to me in applications for PostDoc positions. If someone has not published anything yet, I expect that they will have problems writing manuscripts. I usually contact the references provided with the application – but not always.

MNB: What are your personal deal-breakers in application letters and CVs?

HF: I often end up recruiting people that do not have a straightforward CV but with those that have taken detours and took a bit of time deciding what they are really interested in. Nonetheless, having published does help – and being a nice person.

MNB: At the interview stage, do you ask the applicants to do any hands-on tests?

HF: We usually ask them to present their master thesis or PhD work. Questions on methods / analyses of the data will hopefully show whether they are really competent or not. I have recruited PhD students from abroad where we were only able to have a Skype interview, which prohibited hands-on tests of course. They also presented their work in a talk and I rather asked personal questions to figure out whether they may have problems adjusting to the culture here in Germany.

MNB: In deciding for the successful applicant, what weighs more for you – education and the publication record or the applicant’s personality as you experienced it?

HF: It is a mixture of both. Of course I am trying to find a talented young researcher with excellent skills in doing research and writing. However, the person has to fit into the group as well – so personality is very important to me. We are very space-limited in my group and accidentally recruiting someone who is not a team player my ruin the atmosphere in the group. So the final decision is based on education and publication record as well as gut feeling whether the person fits into the group. The latter is also based on the impression that other group members had of the applicant.

MNB: Do you find the decision-making process in personnel recruitment easy or difficult?

HF: So far recruiting has worked quite well for me – especially when I offered open position directly to people I would like to have in my group. I have had some problematic recruitments though.

MNB: What is your most important advice to young scientists seeking a position?

HF: Only apply to positions where the field of research really interests you – and prepare for the interview by reading up on the research question of the position offered. If you are invited to present your work and group members go out for lunch with you, take the opportunity and ask whether they like the atmosphere of the group etc …

Ferenc Báthori, Hungary, on applying for positions

MNB: When screening announcements of positions, do new challenges rather intimidate or attract you?

FB: In my view, new challenges are attractive as they will allow me to gain new abilities. Furthermore, a new working group always inspires me, thus making it easier for me to handle new challenges.

MNB: In deciding for which positions to apply, what is important for you (the topic, the working group, the geographic location, the salary, etc.)?

FB: A well-fitting topic is the most important criterion in deciding to apply for a new position. Of course, an inspiring, cooperative working group is important, too.The geographic location and the salary are secondary factors for me and the majority of scientists in my working group.

MNB: At the interview stage, are there questions you would rather not be asked, even though they are politically correct, and if so, why?

FB: I think there is no question that would be confusing for me during an interview.

MNB: In considering whether to accept a position you are offered, what weighs more for you – the scientific standing of the employer or the employer’s personality as you experienced it?

FB: The first impression is very important to me. For me, an employer with outgoing personality is always a decisive factor for accepting a new position.

MNB: Do you see a PhD or Postdoc position as part of your education or rather as a paid job?

FB: I think a PhD training is much more part of education. In this period, we have to learn several new skills and abilities that are essential for a succesful academic/research career.

MNB: What is your most important wish for potential employers in deciding for the successful applicant?

FB: My wish is that they make their decision objectively.

Ehab Abouheif, Canada, on recruiting PhD students and Postdocs

MNB: When screening written applications, what are the sections you are most eager to read?

EA: Thinking about how to honestly answer this question made me just realize that I have an unconscious (and therefore biased) formula, which means that I most often look at which school the applicant is applying from and who the applicant has worked with, and then look to see if the applicant has any publications and whether they have a fellowship or not.

MNB: What are your personal deal-breakers in application letters and CVs?

EA: Well, I immediately delete any application letters that don’t start by addressing me by my name, like “Dear Sir”, or address me along with 10 other colleagues in my Department. You may think to yourself “who does that?”, but in fact I still receive quite a few application letters like this, although the frequency has gone down over the years. Once an application letter crosses this threshold, I look to see if the applicant has spent enough time reading my research, meaning I look to see whether they have read a number of my papers and not just the most recent review or paper for example. If I feel the applicant hasn’t spent enough time exploring my approach to understanding ant evolution, I most often send a polite rejection letter. If they have, then I will give the application a closer look, and like I said above, if I have met the applicant or their advisor before, and I am familiar with their institution, then that usually leads to an interview to explore further possibilities for graduate or postdoctoral studies.

MNB: At the interview stage, do you ask the applicants to do any hands-on tests?

EA: Never, but I do ask them to give a presentation on their past research to my lab, and we ask lots of questions!

MNB: In deciding for the successful applicant, what weighs more for you – education and the publication record or the applicant’s personality as you experienced it?

EA: I really see this as a two-step process: the education and publication record get you the interview and invitation to come and visit the lab. After that, it’s all about personality and fit with the lab. Even if the applicant had the best of education, publications and fully-funded fellowship, but I felt that after visiting they were not a good fit for the lab or for the group, I would not accept them into the lab. In contrast, if the applicant has a very positive personality, I would be willing to overlook particular deficiencies because I felt I could work with the applicant to bring them up to speed.

MNB: Do you find the decision-making process in personnel recruitment easy or difficult?

EA: This is one of the trickiest parts of being a Professor and running your own lab. It is especially difficult at the beginning when you lack experience in trying the gauge applicants’ potential for success in research. I still think it’s difficult to predict who will go furthest in the end. We are all human, and each are faced with personal challenges while entering a career in research. Some can overcome any personal challenges and stay focused on the research, while others cannot. So the whole process is somewhat unpredictable.

MNB: What is your most important advice to young scientists seeking a position?

EA: Meeting people and networking is half the battle. So I would highly recommend that undergraduate students wanting to go to graduate school get involved in research early-on. Having a mentor that can speak to your qualities as a researcher is incredibly valuable. Undergraduate students can even organize conferences with their fellow students and invite the people they are excited about meeting and potentially working with. Some universities encourage the undergraduates to do so, and I found this very helpful. For graduate students looking for postdocs, I will make sure to attend seminars, read their papers, and ask to meet with the visiting professors. Go to conferences, present posters and talks, and make sure to talk to those you are interested in working for. When I was a graduate student, I used to make a list of all the professors I wanted to speak to, get familiar with their work, and then during the conference I would walk up to the professors and wait to speak with them. Start off by saying “I admire your work on XXX.” Finally, once given the opportunity to speak to professors you would like to work with, it’s important for prospective students to show their excitement and passion for research, their willingness to work hard, and most important to be humble and show a hunger for learning through mentorship. The best mentors will encourage a healthy disrespect of their ideas. But I digress …

Recent Comments